Authors figured prominently in the first full day of programming at New Voices, New Rooms. Panel themes included humor, horror, and fiction sprung from the South.

Authors figured prominently in the first full day of programming at New Voices, New Rooms. Panel themes included humor, horror, and fiction sprung from the South.

Laughing While Reading

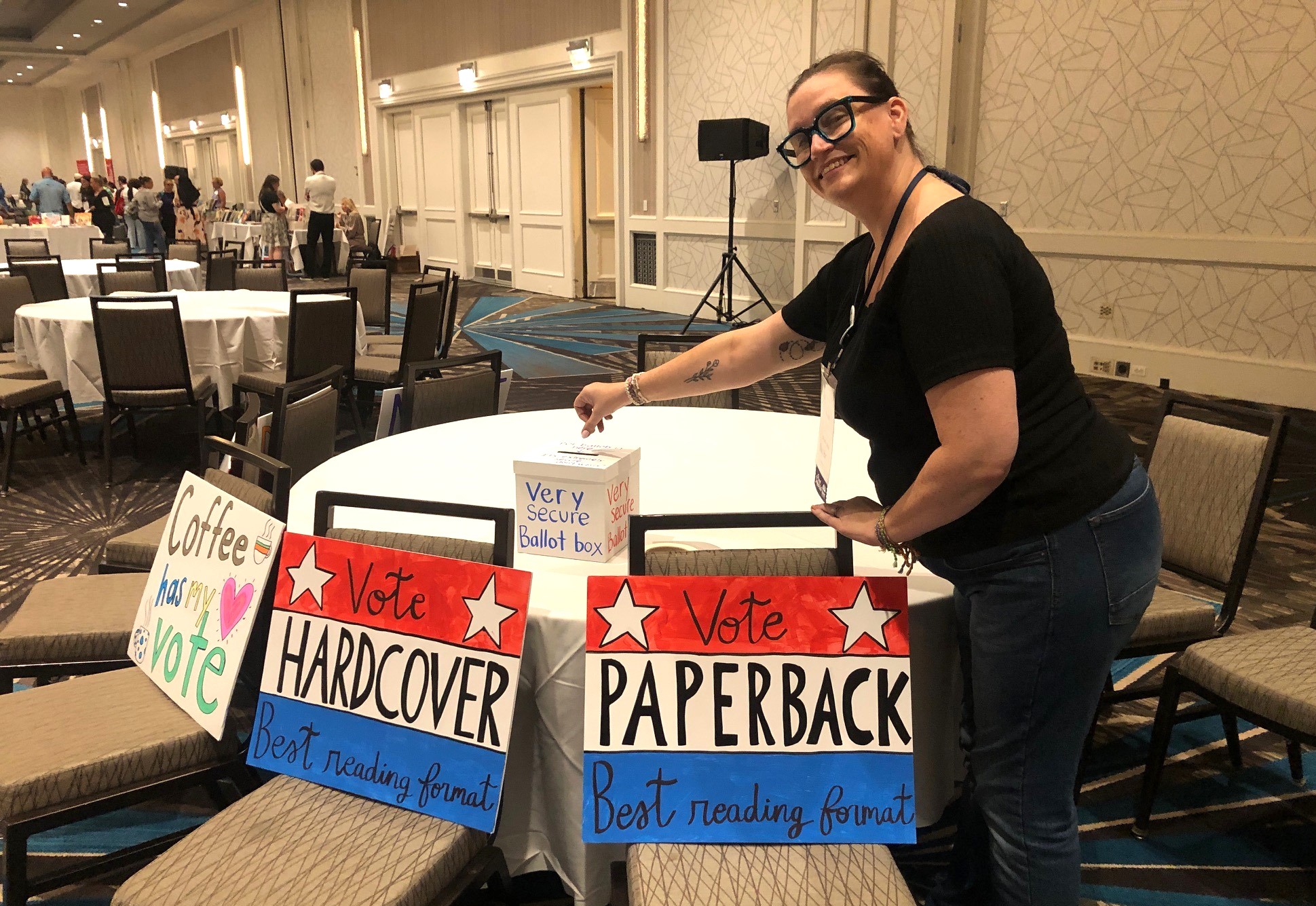

Julie Wernersbach (Hive Mind Books, a traveling bookstore based in Brooklyn, N.Y.) thoughtfully moderated the "Laughing While Reading" panel, featuring two stand-up comics making their book debuts. Scott Seiss (who went viral with his "Angry Retail Guy" posts) channeled his sometimes degrading experiences as an IKEA customer service employee into his book, The Customer Is Always Wrong (Harper Celebrate, Sept. 10). In the book, Seiss says the things you'd occasionally like to say to the customer. Someone begins a complaint, "I've been a customer here for 40 years..." and you respond, "Oh good, then you'll be dead soon," Seiss quipped. In his comedy routines, Seiss does 50 minutes of stand-up, then 10 minutes with his audience, asking them for their worst work stories. One comedy-goer's tale: "My favorite co-worker got arrested for selling cocaine through the drive-thru window." Artist Johnny Sampson's illustrations add another layer of humor. Seiss hopes the book can provide "stress relief" in the break room. (Seiss maintains he's "more polite in real life" than his character in the book.)

|

| Humor authors Scott Seiss (l.) and Phil Hanley with moderator Julie Wernersbach. |

"I'm extremely dyslexic," said Phil Hanley, also a stand-up comedian making his debut, with his memoir Spellbound (Holt, March 18, 2025). "I started in comedy because I didn't have a lot of options." He had no idea what was happening in school. "There were words on the page; that's all I knew," he explained. "I cannot identify a symbol with a sound." But leaving the building for recess was "like walking out at The Tonight Show." He loved the Grateful Dead from the time he was a kid (and later learned frontman Bob Weir is dyslexic): "Each song begins at a jumping-off point, goes as far away as it can, then comes back," Hanley said. "That's what the best comedy does." He got teary speaking of his gratitude toward his mom as he struggled to find his way. It took him six years to write Spellbound. Today he is a big supporter of Eye to Eye, which focuses on student-centered solutions to educating kids with dyslexia, ADHD and other learning challenges.

Horror Writers

The tension between the way things seem on the surface and what lies beneath it emerged as a potent source of horror in a discussion of books by Jill Baguchinsky (So Witches We Became, Little, Brown Books for Young Readers), Linda Codega (Motheater, Erewhon/Kensington, Jan. 21, 2025), and Andrew Joseph White (Compound Fracture, Peachtree, Sept. 3), expertly teased out by moderator Andi Richardson (Fountain Bookstore, Richmond, Va.). Baguchinsky, a Floridian who admits to being a "childless cat lady," set So Witches We Became on a private island off the coast of Florida, where an unexpected guest interrupts a group of high school girls on vacation. The author was tired of watching folks "making excuses for certain people and blaming victims for things," Baguchinsky said. "That's all in there."

|

| Horror authors (from left) Jill Baguchinsky, Linda Codega, Andrew Joseph White, and moderator Andi Richardson. |

Linda Codega's Motheater takes place on the West Virginia/Virginia border, where she said there's a sense of acceptance around mining: "You can't point fingers at any one person or industry. It's a very strange and nuanced area of the world." The book straddles two timelines--the late 1800s and the present day--and draws on "traditional ideas of witches." A woman whose best friend dies in a coal mine is determined to find out what happened. She discovers a half-drowned woman in a mine slough, claiming to be a witch of Appalachia. "Queer horror is about power subversion," Codega said. "There are things in the dark, and you are not paranoid."

"Horror was the only place I felt seen," said Andrew Joseph White. The only place he saw gender dysphoria and autism depicted was in monsters. White's third novel, Compound Fracture, begins after the 2016 election, when the 16-year-old hero is nearly killed. He gets drawn into a 100-year-old controversy in Twist Creek, W.Va., centered on a miners' rebellion that ended in murder by law enforcement. "So much of the history of West Virginia is rooted in social activism," White said, adding that young people "will have to be the changemakers." As the three authors discussed other kinds of books they'd like to write, White pointed out that "horror is parasitic: if you put horror in a romance, it immediately becomes a horror book."

Southern Fiction

"What makes a book Southern?" Lyn Roberts (Square Books, Oxford, Miss.) asked a panel of four Southern writers. Terah Shelton Harris, who spent a semester studying Faulkner, and whose book Long After We Are Gone (Sourcebooks Landmark) was inspired by his As I Lay Dying, did not miss a beat. "Race, religion, sex, and class," Harris said. Terry Roberts (The Devil Hath a Pleasing Shape, Turner, Oct. 1) quipped, "Pat Conroy's South is not my South." He added, "All great works of 20th-century Southern fiction have a dead mule in it." Jamie Quatro (Two-Step Devil, Grove, Sept. 10) said Southern fiction lives at "the intersection of spirituality and sexuality," where "thou-shalt-nots meet permissiveness." Charles B. Fancher said it's the sense of place that's key: "The place you come home to, that nurtures you, and where you're in conflict." He cited James Lee Burke as one of the best when it comes to place.

|

| Southern writers (l.-r.) Terry Roberts, Terah Shelton Harris; Jamie Quatro, and Charles B. Fancher, with moderator Lyn Roberts. |

Harris's Long After We Are Gone quite literally centers on place: the ancestral North Carolina lands of the Solomon family after the death of their father, whom the four surviving children refer to as King Solomon. Harris examines the issues surrounding heir property (the division of land among heirs that makes families vulnerable to wealthy investors who pressure individual family members to sell), which particularly affect Black families in the South. The narrative moves among the viewpoints of the four, revealing complex dynamics and well-guarded secrets.

Asheville, North Carolina's Grove Park Inn provides the backdrop for a tale of "prostitution and politics," as Terry Roberts put it, set 100 years ago, in The Devil Hath a Pleasing Shape. Roberts's third entry in what he calls an "accidental" series stars private investigator Stephen Robbins, here tracing a Jack-the-Ripper figure killing local prostitutes. Robbins's investigation of the naked corpse of a college girl, discovered in the Inn, exposes the societal divide between rich and poor.

An unlikely duo connects--a 70-year-old outsider artist who paints his visions rescues a 14-year-old sex traffic victim--in Jamie Quatro's Two-Step Devil. The artist sees the teen, zip ties on her wrists, in a car in an abandoned gas station and believes he must save her. In describing the book, Quatro cited Ann Patchett's mother's take on Commonwealth: "None of it happened, and all of it is true." Quatro said, "They're all me: the 70-year-old outsider artist, the 14-year-old sex traffic victim, and the devil."

In a similar vein, Charles B. Fancher began Red Clay as narrative nonfiction about his great-grandfather. Readers first meet Felix as an eight-year-old enslaved boy. The tales started as "family anecdotes told to me, and then filtered through me." The book begins as the Civil War draws to a close and continues into the Reconstruction era and the start of Jim Crow. He changed the approach from nonfiction to a novel because "at some point, I realized there were greater truths to be told." Perhaps that is what makes Southern fiction. Grounded in the truth of a place and its people, novels allow the greater truths to be told. --Jennifer M. Brown

Moderator Bunnie Hilliard (center), Brave + Kind Bookshop, Decatur, Ga., zeroed in on the contributions of women in the formation of the present-day United States during Friday's Power and Politics luncheon, when she interviewed authors (l.) Juanita Tolliver (A More Perfect Party: The Night Shirley Chisolm and Diahann Carroll Reshaped Politics, Hachette, February 10, 2025) and Rebecca Graham (Dear Miss Perkins: A Story of Frances Perkins's Efforts to Aid Refugees from Nazi Germany, Citadel/Kensington, January 21, 2025).

Moderator Bunnie Hilliard (center), Brave + Kind Bookshop, Decatur, Ga., zeroed in on the contributions of women in the formation of the present-day United States during Friday's Power and Politics luncheon, when she interviewed authors (l.) Juanita Tolliver (A More Perfect Party: The Night Shirley Chisolm and Diahann Carroll Reshaped Politics, Hachette, February 10, 2025) and Rebecca Graham (Dear Miss Perkins: A Story of Frances Perkins's Efforts to Aid Refugees from Nazi Germany, Citadel/Kensington, January 21, 2025).

V Efua Prince (r.) signed her book Kin: Practically True Stories (Wayne State University Press) for Kelly Rivera, Crooked Shelf Bookshop, Lewistown, Pa.

V Efua Prince (r.) signed her book Kin: Practically True Stories (Wayne State University Press) for Kelly Rivera, Crooked Shelf Bookshop, Lewistown, Pa.

Binc executive director Pam French (r.) announced that Binc had raised $2,970 from booksellers attending NVNR. Suzanne Lucey (Page 158 Books, Wake Forest, N.C.) won Binc's Heads or Tails game, and will donate her $250 winnings to New Kids on the Books Literacy Project, a cause that her bookstore supports. (photo: Ryan Grover)

Binc executive director Pam French (r.) announced that Binc had raised $2,970 from booksellers attending NVNR. Suzanne Lucey (Page 158 Books, Wake Forest, N.C.) won Binc's Heads or Tails game, and will donate her $250 winnings to New Kids on the Books Literacy Project, a cause that her bookstore supports. (photo: Ryan Grover)

Authors figured prominently in the first full day of programming at New Voices, New Rooms. Panel themes included humor, horror, and fiction sprung from the South.

Authors figured prominently in the first full day of programming at New Voices, New Rooms. Panel themes included humor, horror, and fiction sprung from the South.

Some good news from the Bay Area: the

Some good news from the Bay Area: the

Crick, Crack, Crow!

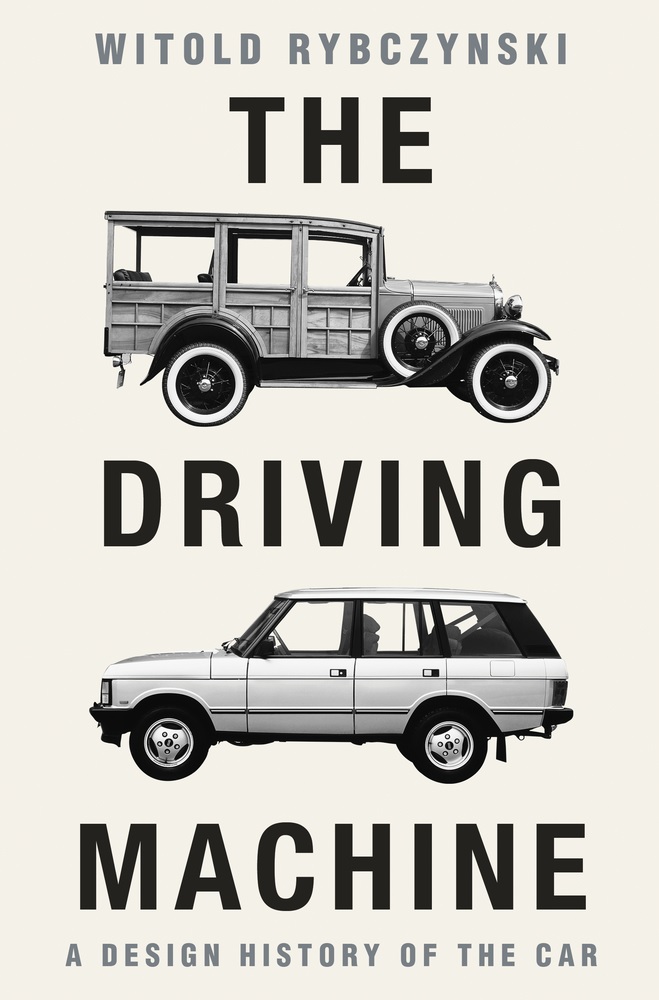

Crick, Crack, Crow! Architect and emeritus professor of urbanism at the University of Pennsylvania, Witold Rybczynski (

Architect and emeritus professor of urbanism at the University of Pennsylvania, Witold Rybczynski (