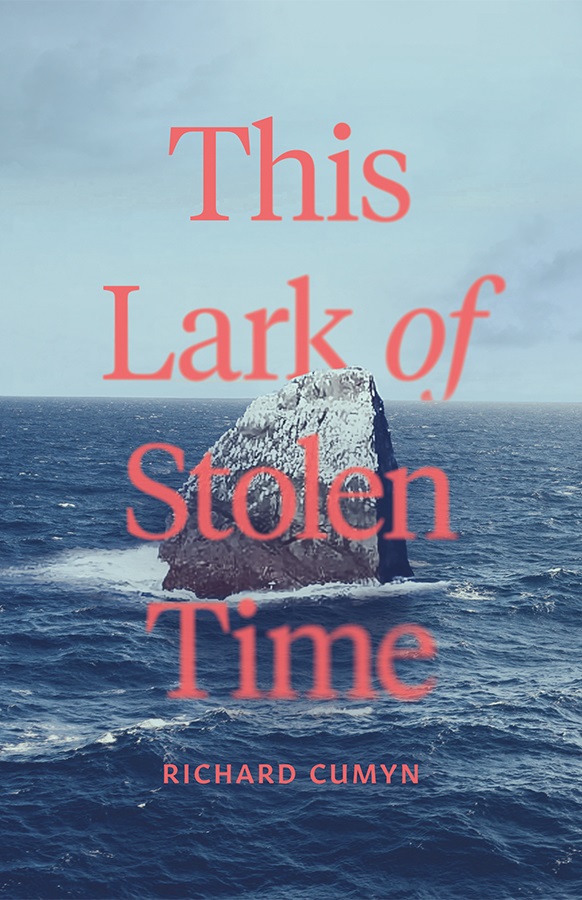

Richard Cumyn is a past fiction editor of the Antigonish Review, and he has been published widely in Canada. He has been shortlisted for the ReLit Award, longlisted for the Frank O'Connor International Short Story Award, and won a Linda Joy Media Arts Award. He lives in Edmonton, Alberta. His 10th book of literary fiction is This Lark of Stolen Time (Great Plains Publications, June 4, 2024), a novel that centers on two Halifax families.

Richard Cumyn is a past fiction editor of the Antigonish Review, and he has been published widely in Canada. He has been shortlisted for the ReLit Award, longlisted for the Frank O'Connor International Short Story Award, and won a Linda Joy Media Arts Award. He lives in Edmonton, Alberta. His 10th book of literary fiction is This Lark of Stolen Time (Great Plains Publications, June 4, 2024), a novel that centers on two Halifax families.

Handsell readers your book in 25 words or less:

Two Halifax households both alike in dignity, bound by love and circumstance. You can go home again but only to catch your breath!

On your nightstand now:

After reading Vivian Gornick's insightful memoir, Unfinished Business: Notes of a Chronic Re-reader, I picked up Sons and Lovers by D.H. Lawrence, almost 50 years after having to read it in high school. We must have been given an abridged version (or I skimmed it) because this time around I am engrossed. A typical writer, I read to plunder (technique more than ideas), and I appreciate the way Lawrence gives Paul Morel's discovery of love the necessary page-space to unfold naturally.

On deck is The Sentence by Louise Erdrich. I love bookstore stories--Penelope Fitzgerald's The Bookshop is a favorite--and, according to my wife, Sharon, who devoured The Sentence and said, "You MUST read this novel," it's also a ghost story. What could be better?

Favorite book when you were a child:

The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame. I discovered it on my own at age 11 and was so enthralled by the story of Toad, Rat, and Mole that I wrote an imitative story about the origin of the duckbilled platypus.

Your top five authors:

I will read anything by Ian McEwan, that consummate blend of literary stylist and storyteller who keeps you up at night. I will spend the remainder of my days trying to figure out how Alice Munro constructs her stories. I turn to Mavis Gallant to hear her uncompromising voice delineate the sharp edges and the sweep of life. Penelope Fitzgerald for her piquant humor. James Salter writes about masculinity with a sophistication that eschews stereotype and suggests how men might raise their sights above crudeness and mindless violence.

Book you're an evangelist for:

Two by James Salter: Light Years, for its crystalline depiction of natural beauty, and its calm, adult investigation of the dissolution of a marriage; and A Sport and a Pastime, about a young American discovering (wink, wink!) all the pleasures of rural France after the war.

Book you've bought for the cover:

The Roaring Girl by Greg Hollingshead, which won the 1995 Governor General's Award for fiction. The bonus was that, once past the fetching lass seated cross-legged in her abbreviated red dress, I devoured the stories. More plunder for the fledgling writer.

Book you hid from your parents:

Book you hid from your parents:

It was actually a book my father had hidden from my brothers and me in his dresser drawer: Fanny Hill: Or, Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure by John Cleland. I became adept at lifting it, reading a chapter, and returning it undetected to its rather obvious cache. For 18th-century porn, it was surprisingly literate and, for a teenage boy desperate to learn about sex, titillatingly accurate and instructive.

Book that changed your life:

I read Barry Hannah's collection Airships at a time in my life when I was ready to commit to being a writer and to experiment with something wilder and more poetic in my prose. Hannah taught me that exuberance, even controlled craziness, was allowed a writer if it was in faithful service to the spirit of the story.

Favorite lines from books:

"A rather rusted sensitivity served to bar her progression into tactlessness," from Janet Frame's delightful novel, In the Memorial Room, is the kind of double-edge wordplay that stops me in my tracks, willingly, just to savor the wit.

"I see you riding down from the mountains to the desert at that hour when thunderstorms and sunsets caparison the sky...." This is in a letter from J. Robert Oppenheimer to Herbert Smith, his former teacher at the Ethical Culture School. He's describing his beloved Los Alamos, N.Mex. We may have seen the Oscar-winning movie, but the book on which it was based, American Prometheus by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, makes Oppenheimer the man so much more understandable in all his troubled complexity. I had to look up the word "caparison," which is an ornamental covering for a horse.

Five books you'll never part with:

I'm not slavishly proprietary about books, which have a way of multiplying and complicating one's living space. But there are a few that I need to know are nearby:

One is an illustrated edition of Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe, inscribed to my maternal grandfather on his birthday from his father and dated 1896. One day I would like to have it rebound and preserved before I pass it along.

I cherish a signed copy of my dear friend, the late Steven Heighton's story collection, On earth as it is. On the title page he has drawn a map of eastern Canada and traced a dotted line from Nova Scotia, where we had been living, to Ontario, where we had just moved for Sharon's work. Labeled spots are, "1. a broken man on a Halifax pier" and "2. a frozen man on Collingwood Street" in Kingston, the city where Steve lived.

In 1968, I won an Ottawa Humane Society essay contest. The prize was Paul Gallico's gem of a book, The Snow Goose, which culminates in the civilian mobilization to rescue stranded Allied soldiers on the beaches of Dunkirk in 1940. Its musical sentences, too, made me want to write.

My brother Alan Cumyn's timeless YA novel The Secret Life of Owen Skye is dear to me, because it encapsulates the essence of pre-teen boyhood in all its sweet naivety, and because it draws upon some of Alan's, our brother Steve's, and my quasi-heroic childhood escapades.

I will also hold on to my signed first edition of The Birth House by Ami McKay. She and I were paired in one of the first years of the mentorship program run by the Writers' Federation of Nova Scotia and endowed by a generous gift from Alistair MacLeod after the success of his stirring novel No Great Mischief. Ami and I would meet weekly, either in her home, which had been the midwife's house in Scots Bay, or in Halifax, to talk about the progress of her novel. I'm proud to have played a small part in the creation of such a beloved book.

Book you most want to read again for the first time:

Michael Ondaatje's The English Patient. When poets write novels, the rest of us need only stand aside and watch. Every scene, from the Bedouin healer arriving with his clinking bottles of medicines and salves, to the breath-stopping tension of landmine detection, is unforgettable.

Book publication you are most excited about:

I recognized in Rosalind Brown an original talent immediately upon reading her novel excerpt, "A Narrow Room," in the Fall 2023 Paris Review. Brown takes the simple, familiar premise of a student trying to write an essay about Shakespeare's sonnets, and turns it into something so immediate, sensual, and smart that I blush with embarrassment to think about my mediocre undergraduate attempts to do the same. Rosalind Brown's Practice should be in bookstores soon.

I'm also eager to read Michael Ondaatje's new poetry book, A Year of Last Things. In his poem, "Definition," published recently in the New Yorker, he dream-raids a Sanskrit dictionary for such entries as "A single word to portray light/ from that distant village/ reflected in a cloud,/ or your lover's face lit/ by the moonlight on a stage."

At Children's Institute 2024 last week in New Orleans, La., four booksellers convened to discuss the intersection of advocacy, activism, and bookselling. The panel featured Rebecca Crosswhite, co-owner of

At Children's Institute 2024 last week in New Orleans, La., four booksellers convened to discuss the intersection of advocacy, activism, and bookselling. The panel featured Rebecca Crosswhite, co-owner of

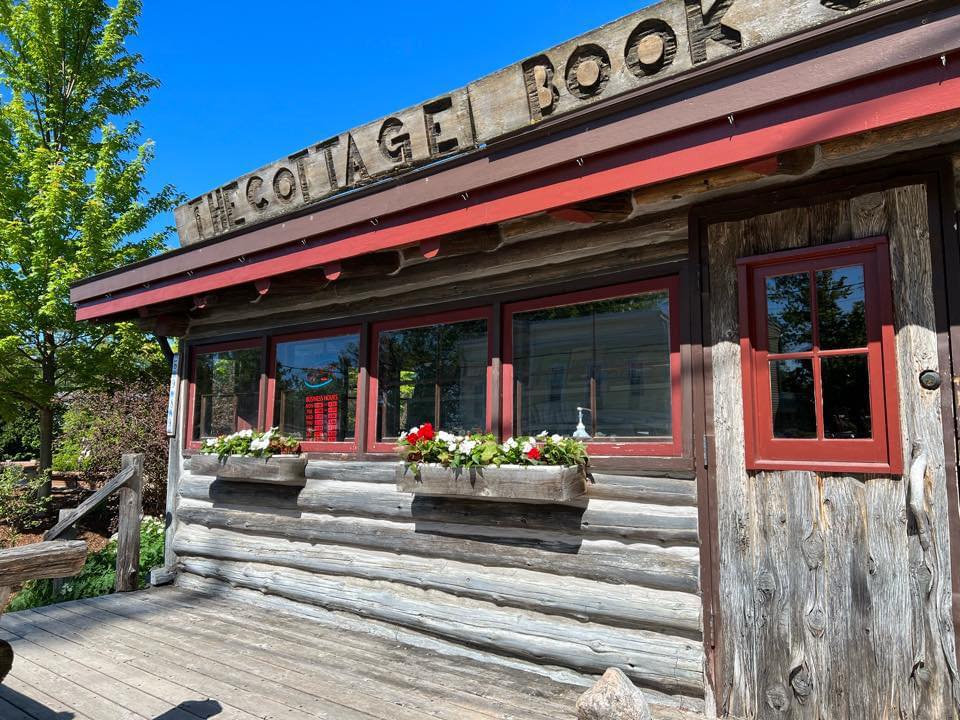

Author Ann M. Martin, surrounded by staff (and bookstore dog Delta) at her local indie,

Author Ann M. Martin, surrounded by staff (and bookstore dog Delta) at her local indie,  "All You Need Is Love... and Books, Don't Forget Books!"

"All You Need Is Love... and Books, Don't Forget Books!"

Pearce Oysters: A Novel

Pearce Oysters: A Novel Richard Cumyn is a past fiction editor of the Antigonish Review, and he has been published widely in Canada. He has been shortlisted for the ReLit Award, longlisted for the Frank O'Connor International Short Story Award, and won a Linda Joy Media Arts Award. He lives in Edmonton, Alberta. His 10th book of literary fiction is This Lark of Stolen Time (Great Plains Publications, June 4, 2024), a novel that centers on two Halifax families.

Richard Cumyn is a past fiction editor of the Antigonish Review, and he has been published widely in Canada. He has been shortlisted for the ReLit Award, longlisted for the Frank O'Connor International Short Story Award, and won a Linda Joy Media Arts Award. He lives in Edmonton, Alberta. His 10th book of literary fiction is This Lark of Stolen Time (Great Plains Publications, June 4, 2024), a novel that centers on two Halifax families. Book you hid from your parents:

Book you hid from your parents: Immortal Dark is a fabulously bloody and intricate reimagining of the vampire myth, wherein an ancient agreement between vampires--or "dranaics"--and humans is all that keeps a massive slaughter of mortals at bay. But the stasis becomes threatened when one bitter, self-destructive 19-year-old embarks on a mission to save her twin, no matter the cost.

Immortal Dark is a fabulously bloody and intricate reimagining of the vampire myth, wherein an ancient agreement between vampires--or "dranaics"--and humans is all that keeps a massive slaughter of mortals at bay. But the stasis becomes threatened when one bitter, self-destructive 19-year-old embarks on a mission to save her twin, no matter the cost.