Friday, April 15, 2022

Welcome back to our new look! Your favorites are still here--reviews of the best books out this week, Book Candy, Writer's Life and Rediscover--along with some new features.

In this issue, we review Take My Hand by Dolen Perkins-Valdez, in which a 1970s Alabama nurse uncovers a miscarriage of justice; Jordan Crane's graphic novel love story Keeping Two; and Nancy Werlin's middle-grade Healer and Witch, about a young woman with magical powers in medieval France. Plus, Claire Kohda describes how her pandemic experience contributed to the vampire protagonist in her debut novel, Woman, Eating.

Take My Hand

by Dolen Perkins-Valdez

Equipped with a startling ability to draw graceful fiction from grotesque history, Dolen Perkins-Valdez (Wench; Balm) brings her talents to the 1970s in Take My Hand, a novel probing the fallout of stolen autonomy and misogynoir. In the first chapter, narrator Civil Townsend admits: "I'm not trying to change the past. I'm telling it in order to lay these ghosts to rest." The ghosts this young nurse in Montgomery, Ala., unearths are malicious. Assigned to administer birth control to two Black girls living in extreme poverty, Civil soon discovers that the girls have been sterilized involuntarily and that they are but two within a larger network of Black women who have been subjected to the crime. Civil, hellbent on finding the truth and ensuring it is dragged into the open, fights to learn the full extent of what has happened to the women of her community--and how much she may have been complicit.

Perkins-Valdez ushers in this central conflict slowly and methodically; when it arrives, the revelations that follow are unforgettable. As she writes in her author's note, "My hope is that this novel will provoke discussions about culpability in a society that still deems poor, Black, and disabled as categories unfit for motherhood." Readers will find it impossible to take in even a chapter without their gut twisting in recognition; the ghosts of these horrors are still alive today. Take My Hand solidifies how essential it is that their stories continue to be told. --Lauren Puckett, freelance writer

Discover: A nurse in Montgomery, Ala., stumbles upon an atrocious miscarriage of justice in this evocative tale.

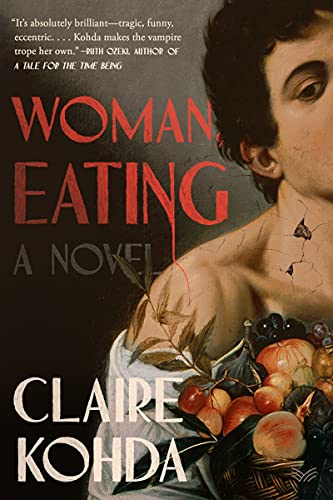

Woman, Eating: A Literary Vampire Novel

by Claire Kohda

Claire Kohda's debut, Woman, Eating, is an insightful and hypnotic exploration of hunger. Its young vampire protagonist, Lydia, a recent art school graduate, is starved--not only for blood but for belonging.

Lydia's obsessive consumption of YouTube food videos to try to satiate this intractable hunger is the perfect analogy of vampire yearning. Her inability to eat isolates her from her human coworkers and prevents her from experiencing a vital part of her paternal, Japanese culture. As she ponders, while watching what a particular fashion model eats in one day, many of these videos feel educational: "Lots of them take that tone, as though their message is: if you eat like me, you will become me."

Through Lydia's mixed-race heritage and particular vampire traits, Kohda deftly tackles difficult, and common, themes--including sexism, racism, assault, job insecurity and social isolation. Despite her supernatural powers, Lydia struggles with feelings of helplessness and vulnerability as she navigates these experiences and seeks ways to discover her own voice, purpose and strength.

"The urge I feel is to return to painting... and to see if I can find the shape of myself in whatever I create." The use of art as a tool for this self-discovery is one of the many highlights of Woman, Eating. It is a way for Lydia to share herself with the humans around her, independent of her vampire mother's expectations, while simultaneously helping her feel kinship with her human, artist father. --Grace Rajendran, freelance reviewer and literary events producer

Discover: This compelling exploration of the need for belonging is told from the intriguing point of view of a vampire.

People from Bloomington

by Budi Darma, transl. by Tiffany Tsao

More than four decades after its Indonesian debut, the fascinating People from Bloomington by Budi Darma (1937-2021), one of Indonesia's most lauded authors, arrives for English-language readers. Darma (Conversations) wrote these seven stories in peripatetic jaunts between 1976 and 1979, when he was a master's and then Ph.D. student at Indiana University in Bloomington. This edition opens with 40 essential pages, which include feminist writer/academic Intan Paramaditha's edifying foreword, novelist/translator Tiffany Tsao's discerning introduction and a "lightly revised" version of Darma's original 1980 preface.

Jane Austen was the subject of Darma's Ph.D. thesis, and his book includes many nods to Austen's novels, as well as other Western classics. Each story is revealed through a male, first-person narrator; most are students living in transitional rental housing. Absurd and often threatening situations loom and feature an aging World War II veteran wandering town with a pistol; a man's slyly vicious attacks on a neighboring family; and a man who unintentionally discovers his biological father and orchestrates his demise.

If the Western canon is rife with exotification of the other, this short story collection is especially rare for its Asian author writing about everyday American Midwesterners. In Darma's acknowledgments, written in 2020, both Paramaditha and Tsao (The Majesties) win praise for putting his collection in a global context: "Paramaditha for her succinct reflection... in relation to Indonesian literature" and Tsao for "her analysis... with respect to Western literature in general and English literature in particular." Beyond the specificities of Bloomington, each of Darma's narratives heightens the universal human longing for connection. --Terry Hong, Smithsonian BookDragon

Discover: Forty-plus years after its initial publication, Budi Darma's mesmerizing Indonesian classic--ironically, about American Midwesterners--arrives in its first English translation.

At the Edge of the Woods

by Masatsugu Ono, transl. by Juliet Winters Carpenter

At the Edge of the Woods is a haunting fable about the disturbing strangeness of modern life. Masatsugu Ono (Echo on the Bay) avoids names and specifics, which adds to the novel's amorphous unpredictability. The novel, translated from the Japanese by Juliet Winters Carpenter, follows a family of three: a father and son in their house at the edge of the woods, the mother embarking on a trip to give birth to her second child.

Ono freely mixes fantastical elements into the story. The titular woods are reminiscent of dark fairy tales, supposedly containing imps and a "castle" that once served as the headquarters for an unspecified Resistance. The woods are made unnervingly animate at every turn, as when Ono writes: "the trees on either side, dense with foliage, gave the impression they were falling toward us, one after another." Or when the father complains of an insistent coughing coming from the woods. The grim, almost vengeful atmosphere, combined with the sight of floods and refugees on television, suggests that the novel might operate as an allegory for climate change or other ecological crises. At the Edge of the Woods is too mysterious to be fully pinned down, however.

The novel takes on an episodic feel, created by various characters who wander in and out of the narrative. It also has an odd sense of humor, often presenting an acerbic angle on everyday life. Its most lasting impression might be the anxious mood that pervades the novel, the sense of the world as irrational, unknowable and threatening. Some readers might think At the Edge of the Woods has perfectly captured the mood of the times. --Hank Stephenson, the Sun magazine, manuscript reader

Discover: In an eerie, fable-like novel, a family lives beside a forest filled with mysteries and an indefinable, threatening aura.

Romance

The No-Show

by Beth O'Leary

Beth O'Leary (The Switch; The Flatshare) presents another beautifully nuanced romance in The No-Show. Not as comedic as some of O'Leary's other novels, this is a lovely look at the nature of love and how to tell if someone is the right person for right now--or the right person for always.

The No-Show revolves around three young British women, strangers to one another and living vastly different lives. Siobhan is a fierce and outspoken life coach, enjoying the whirlwind of modern dating; Jane is a timid, nervous charity shop employee, who uses her strict routines to keep her grounded; and Miranda is a gutsy tree surgeon, who is okay with just being one of the guys. But they all have one thing in common: they were stood up on Valentine's Day and, as it turns out, they were all ghosted by the same man. As the three women untangle their feelings for their date and the dramas happening in their own lives, O'Leary uses their widely varied personalities to explore love from multiple perspectives.

Poignant and compelling--and surprisingly informative about the risks arborists undertake--The No-Show is an engrossing novel. Readers are sure to have strong opinions about who should end up with whom as the story moves among the lives of Siobhan, Jane and Miranda--and the man they're all dating. O'Leary does an excellent job, as always, of creating a charming, realistically flawed romance, while simultaneously tapping into the darkly funny side of life. --Jessica Howard, freelance book reviewer

Discover: In this clever rom-com from the author of The Flatshare, three very different British women discover they have one thing in common: they're dating the same man.

Just the Two of Us

by Jo Wilde

Jo Wilde's sweet and engaging Just the Two of Us manages to be both a pandemic love story and a thoughtful look at the ups and downs of a long marriage. Julie Marshall is on the brink of serving her husband, Michael, with divorce papers in March 2020 when the lockdown necessitated by the Covid-19 pandemic forces them to stay at home together. After nearly 35 years, their relationship has gone cold and they have grown distant, especially since the death of Julie's mother. But with Julie's flower shop closed and their three grown children all isolating elsewhere, the couple begin to reflect on the life they've built and wonder if they can find a way back--or possibly forward--together.

Though Wilde's narrative tone is light, she deftly captures the odd panic of early pandemic days: the hours of silence, the constant worry about virus transmission and the desire for even a bit of in-person company. She also paints a nuanced picture of two people who have always deeply loved each other but who have lost the former joy they took in each other's presence. Wilde (Four Minutes to Save a Life, writing as Anna Stuart) captures the mixture of grief, longing, nostalgia and attempts to move forward through small moments: a picnic in the garage with Michael's beloved motorbike, an impromptu waltz in the living room and halting conversations that sometimes stall but are believably heartfelt. Readers will root for Julie and Michael to not only make it through the pandemic but also make it to their 35th wedding anniversary--and to all the years beyond. --Katie Noah Gibson, blogger at Cakes, Tea and Dreams

Discover: Jo Wilde tells a nuanced, heartfelt story of a long marriage on the brink of divorce during the early part of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Graphic Books

Keeping Two

by Jordan Crane

Jordan Crane (The Last Lonely Saturday) spent more than two decades creating Keeping Two, a magnificently multilayered graphic novel that empathically addresses the universal human fears of losing those most beloved. In the course of a single evening, the story introduces, challenges and reconnects two lovers, Connie and Will.

The couple arrives home from a long and exhausting drive. "We should take the train next time," Will says as they close the front door. After checking their phone messages and then returning calls, they learn of two deaths. Will insists deaths happen in threes but, superstitions aside, their immediate hunger inspires a deal: Connie will go to the store and pick up a movie, while Will commits to cleaning the massive piles of dirty dishes. They part with a casual "I'll see you in a little bit," but their reunion doesn't happen for hours and hours--and hundreds of pages--plenty of time to imagine every worst-case scenario. In between, Crane brilliantly reveals their contentious road trip, the book they've been reading out loud along the way (watch for ever-so-subtle shifts) and the callers with their sad stories.

Crane presents his panels--mostly six-on-a-page--in an unusual palette of lime-to-forest green washes over line drawings. Nature, especially plants and trees, is hinted at throughout, culminating in magical woody scenes near the story's end. The final page with publication data adds, "Forest Stewardship Council certified," as if a last reminder of protecting life. While the "rule of threes" looms, for these lovers' sake, two is plenty enough. --Terry Hong, Smithsonian BookDragon

Discover: Jordan Crane's glorious graphic love story empathically confronts the very human fear of losing those most beloved.

Biography & Memoir

Tasha: A Son's Memoir

by Brian Morton

In Tasha, Brian Morton (Florence Gordon) offers up a biography wrapped in a memoir, an attempt to understand the complex and complicated woman his late mother was.

Morton starts with his own understanding of his mother. He recalls her harebrained adventures as a young mother, their strained but never estranged relationship as he became an adult, and later her slow decline into depression and "despondency" following the sudden death of her husband, Morton's father. "When you're young, it's hard to see your parents in context," Morton writes. "Your parents are the context." Following years of complicated caregiving as his mother aged, and her eventual death, he yearns to understand his mother. Thus was born Tasha, an attempt "to see her whole, as I didn't succeed in doing when she was alive."

Tasha Morton was the first-ever copy girl at a local newspaper. She paused her education for 10 years to mother her two children before eventually earning a master's degree and starting a career as a teacher in her 40s. She attended the board of education meetings in her town every week, served on the board for 20 years until the age of 80, and kept attending meetings even after failing to win re-election in 2005. She organized against racist redlining practices in her town.

Morton offers up these accomplishments as context before focusing more fully on his mother's eventual stroke and slow decline toward death. Tasha is a beautiful and kind, if not always nice, tribute to a mother from her son, told with a quality of self-reflective honesty that is at once heartbreaking and heartwarming. --Kerry McHugh, freelance writer

Discover: From the author of Florence Gordon comes a moving memoir of a son's relationship with his complicated mother.

Political Science

The Age of the Strongman: How the Cult of the Leader Threatens Democracy Around the World

by Gideon Rachman

As revealed in the disturbing reappearance of the "strongman" leader, the past two decades have witnessed the alarming international rise of authoritarianism. This, according to Orwell award and European Press Prize-winning journalist Gideon Rachman in The Age of the Strongman: How the Cult of the Leader Threatens Democracy Around the World, poses a dire challenge to the survival of liberal democracy. Indeed, in the last 20 years "a process of democratic erosion has set in" around the world, thanks to the rise of political strongmen who characteristically place their "instincts above the law and institutions."

The rogues' gallery of strongman leaders Rachman analyzes is a familiar list, with a few surprises thrown in that will stir some debate. Beginning with the 2000 election of Vladimir Putin to the Russian presidency, Rachman sets a brisk pace on this bleak journey of today's most threatening world leaders: Recep Erdoğan, Xi Jinping, Viktor Orbán, former U.S. president Donald Trump, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, Rodrigo Duterte, Jair Bolsonaro, Narendra Modi, Abiy Ahmed and Boris Johnson (a dubious inclusion). While oceans of ink have been spilled on these politicians on an individual basis, Rachman (Easternisation: War and Peace in the Asian Century) finds a universal coherence in the strongman playbook that can instruct those nations wishing to resist. The "four cross-cutting characteristics" are: the deliberate creation of a cult of personality; disdain for the rule of law; an attempt to represent "the real people" against elites; and fear-based politics that elevate nationalism. This cogent study provides a timely (and chilling) examination of the strongman leader and how freedom-loving societies should respond. --Peggy Kurkowski, book reviewer and copywriter in Denver, Colo.

Discover: A veteran journalist probes the chilling similarities in the world's leading strongmen and the threat they pose for peace, world order and the survival of liberal democracy.

Body, Mind & Spirit

Richard Wagamese Selected: What Comes from Spirit

by Richard Wagamese and Drew Hayden Taylor, editor

Award-winning Ojibway novelist and journalist Richard Wagamese (Indian Horse), who died in 2017, is considered an integral part of the "Indigenous literary universe." As editor Drew Hayden Taylor notes in the introduction to Richard Wagamese Selected: What Comes from Spirit, "it is perhaps Richard Wagamese who has captured the Canadian zeitgeist best of all us Indigenous writers." Wagamese's works, which blend his vast life experience and his many reflections on the world as it was and how it might yet be, have spanned genres and platforms. Richard Wagamese Selected brings together thoughts and writings from his blog, his newspaper columns and even his social media to give readers an inspiring look into his philosophies on living.

The book is loosely organized into four sections. His writings testify to the cruelties to Indigenous families committed by the Canadian government as well as how institutional decisions added to and compounded the complexities in his life. But he also shares his decision to reconnect with his culture and explains how, in making active choices, those faced with systemic injustices might avoid becoming cruel themselves. He writes: "Never forget that we carry a common practical magic within us; that we are star dust and we carry comets and whirlwinds inside of us. That we are all magical beings--and we always were." A hopeful, meditative tone dominates. This is a collection to be savored slowly, as readers allow what Wagamese shares to sink in under the noise of modern life. --Michelle Anya Anjirbag, freelance reviewer

Discover: This inspiring collection of Richard Wagamese's nonfiction writings and essays, presented in a single volume, shows readers the man behind the novels.

Children's & Young Adult

Healer and Witch

by Nancy Werlin

YA author Nancy Werlin's middle-grade debut is an unhurried and subtle bildungsroman that features a young woman trying to understand her magical powers in medieval France. Healer and Witch gracefully explores themes of identity, family and belonging.

Fifteen-year-old Sylvie comes from a long line of strong women and healers. She, her mother and her grandmother are trusted in the village of Bresnois to treat injuries and illnesses. However, Sylvie's ability to view and manipulate the memories of others goes beyond ordinary healing. When Sylvie's grandmother dies unexpectedly, Sylvie attempts to use magic to cure her mother's grief--with disastrous results. Desperate to fix her mistake, Sylvie leaves Bresnois in search of "someone who could help her with her gift." Sylvie's quest introduces her to new friends, including a mischievous stowaway, a stern yet kind young merchant and a self-proclaimed witch. Far away from "everything she knew," Sylvie comes to realize that the true nature of her power may be something only she can determine for herself.

There are no epic battles or grand prophecies in Healer and Witch, whose fantasy narrative remains grounded in the human stakes facing Sylvie and her companions. Werlin (Zoe Rosenthal Is Not Lawful Good) brings compassion and complexity to her depictions of the relationships between characters. No individual is defined by a single trait and first appearances often prove misleading. Indeed, a recurring message is that positive and negative experiences are part of a full life, and repressing feelings of unhappiness can be harmful rather than helpful. Readers looking for a gentle, understated historical fantasy will sympathize with Sylvie in her struggle to "choose her own future" in a "world that was increasingly hostile to women such as herself." --Alanna Felton, freelance reviewer

Discover: A young woman's quest to understand her magic powers leads to self-discovery, healing and unexpected friendships in this emotionally sophisticated middle-grade fantasy.

Kitty

by Rebecca Jordan-Glum

With Kitty, Rebecca Jordan-Glum (The Trouble with Penguins) makes a funny/goofy picture book contribution to a long-standing comedy tradition: mistaken identity caused by clouded vision.

"Don't worry about a thing," pet-sitting Granny tells her grandkids as they're leaving the house. "The cat will be just fine!" Sure, but what about Granny? When stripy-tailed cat Satsuki has a scare and leaps from atop the refrigerator, Granny's glasses go flying. Fortunately, she can still read the pet-care instructions that her grandkids left for her: "Please don't let the cat out." But uh-oh: Satsuki is already out the door. Granny's got this--or so she thinks: using cat food as bait, she entices a stripy-tailed critter back indoors, only it isn't Satsuki. Unbeknownst to visually challenged Granny, the creature is a neighborhood raccoon, and it proceeds to wreak havoc on the house and her nerves.

Jordan-Glum's text is spare, her jokes either marvelously underplayed (the omniscient narrator refers to the raccoon as "Kitty") or purely visual (the attentive reader will spot Kitty modeling Granny's glasses). In a devilish juxtaposition, the Satsuki-care instructions, which declare the cat to be "very sweet!," sit among the rubble in a room being trashed by the sweetness-impaired raccoon. Kitty is teeming with other choice visual touches, including cute curios like penguin salt-and-pepper shakers, color-bursting vintage-style wallpaper and intermittent glimpses of Satsuki, who, peering in the window, enjoys the show. --Nell Beram, freelance writer and YA author

Discover: This witty/wacky picture book teems with sight gags, starting with the central one: pet-sitting Granny loses her glasses and mistakes a neighborhood raccoon for her grandkids' cat.

An Arrow to the Moon

by Emily X.R. Pan

An Arrow to the Moon is an incandescent YA retelling of Romeo and Juliet infused with Chinese mythology. Emily X.R. Pan's singular storytelling makes this fantasy distinctive and romantic.

Luna Chang's parents consider her a blessing, though lately Luna feels crushed by their expectations. Hunter Yee is "a wayward star, shooting in the wrong direction," whose angry parents, on the run from some scary "random dude," are always finding fault with him. The two sets of parents despise each other but when Luna and Hunter meet, Luna immediately has the "magnetic and bizarre" feeling that they're being pulled together; Hunter forgets to breathe. The teens feel at peace together even as the ground splits open and a mysterious crack begins to snake through Fairbridge, their otherwise nondescript town. As the cracks multiply, Luna and Hunter realize they may have set something ancient into motion. When an old associate of Hunter's parents arrives on the scene, the danger escalates: Hunter's parents need to disappear once again, time feels as if it's "coming to an end" and the entire world seems filled with "wrongness." Luna and Hunter reluctantly begin trying to understand the phenomenon, fearing they may be the only ones who can fix it.

In this reinterpretation, Pan (The Astonishing Color of After) perfectly blends Shakespearean tragedy with traditional Chinese myths about a girl who guards the moon and a "boy who made the stars fly." Vivid imagery infuses her tale with an otherworldly magic, even as her characters seem grounded in their present-day, suburban town. Fantasy lovers should adore this enchanting novel. --Lynn Becker, reviewer, blogger, and children's book author

Discover: This luminous, romantic tale of young love is a Chinese mythology-influenced Romeo and Juliet set in a mundane suburban town.

New in Paperback

The Writer's Life

Claire Kohda: Of Blood and Belonging

|

|

| (photo: M. Gafarova) | |

British writer and musician Claire Kohda reviews books for the Guardian, the TLS and elsewhere. She recently spoke with Shelf Awareness about her own debut, Woman, Eating: A Literary Vampire Novel (HarperVia, $26.99; reviewed in this issue), starring Lydia, a recent art school graduate starving as much for belonging as for blood.

Although she is a vampire, Lydia has many "human" worries and insecurities. Why was it important for you to tell a vampire story in this way?

I wrote this novel just under a year into the pandemic; for all of us, our worlds had shrunk. Lydia--the isolation she feels as a vampire living in a world of humans--came out of that time. We need human contact to feel human ourselves. I had my partner and my cat, but the longer lockdowns went on, the more I felt like an animal, living in a little den, creeping out sometimes, but fearing other people. When things started opening up again, I think a lot of people felt like they'd forgotten how to exist in human society. That's Lydia's reality; she's always aware of what makes her different. It's like she's living in a world that isn't designed for her.

The vampire, as a mythical figure, is inherently in between multiple things. When a vampire is turned, it retains its human body and its human memories, but gains this demonic appetite; so, it exists between human and demon. It exists between life and death, good and evil, too. Vampires, traditionally, also can't eat food. They have to drink blood to survive. And, for us humans, food is so crucial, not only as sustenance, but culturally--it's a form of communication: we pass down recipes from generation to generation, we share food with friends and family. The vampire has none of that. What would it really be like to exist like that?

Lydia is both mixed-race and a vampire and feels like an outsider in all her worlds. What was the inspiration to share this perspective?

Ultimately, the only thing that sets a vampire apart from a human is diet--and I found that fascinating. Cuisine is so often used as a means to Other people from Asian cultures. We saw it in James Corden's "Spill Your Guts" segment on the Late Late Show--Asian cuisines are presented as disgusting and weird, and that rubs off on how people perceive Asian people. But Asian cuisines are also often perceived as crueler, too, and therefore the people are perceived in the same way. Despite my being a vegan, strangers (and sometimes people I know) who find out I am part Japanese will ask me about, and sometimes even hold me responsible for, whaling, or dog meat farms in other parts of Asia.

In reality, Lydia is no different from us. She is as human as can be. She cares about being good, she even sources her pigs' blood from RSPCA-certified farms. But if she revealed herself to be a vampire, people would see her as a monster, they'd fear her. That fascinated me--the idea of creating something so solidified in our minds as being monstrous that actually is the opposite. She's relatable, and she's deeply empathetic and caring. Lydia is just a different species to us; she's a kind of manifestation of what it's like to be different, and of what it's like to be feared or to struggle with your identity, because of that difference.

In reality, Lydia is no different from us. She is as human as can be. She cares about being good, she even sources her pigs' blood from RSPCA-certified farms. But if she revealed herself to be a vampire, people would see her as a monster, they'd fear her. That fascinated me--the idea of creating something so solidified in our minds as being monstrous that actually is the opposite. She's relatable, and she's deeply empathetic and caring. Lydia is just a different species to us; she's a kind of manifestation of what it's like to be different, and of what it's like to be feared or to struggle with your identity, because of that difference.

You wrote this around the onset of the pandemic, when there was an increase in Asian hate crimes. Did any of that influence your writing?

Yes, definitely. I wrote Woman, Eating at the end of 2020. It had been almost a year of increased hate crimes against East and Southeast Asians. My mum, my Asian friends, fellow Asian musicians--all of them had experienced at least some form of racism during the pandemic, whether it was a boss wondering out loud if they should not have shifts in their public-facing job because their Asian-ness might put customers off, people blaming Asians for the pandemic, telling them to get off trains, or physically assaulting and verbally harassing people of Asian heritage. I believe it fed into what I wrote.

There's nothing like hearing about racism experienced by a parent that makes you feel a confusing mix of two emotional extremes--rage and anger, but also helplessness and futility. Wanting to defend that parent but also knowing that racism is deeply rooted, and anything you do won't fix the wider problem, can be so debilitating and exhausting. Lydia is like an embodiment of those two feelings--she's got the power and strength to be able to retaliate, but she's also got a lot of things that weigh on her (looking out for her mother, the legacy of colonialism in Malaysia both by her father's and grandfather's countries, racism in the U.K.). At times, they seem like physical weights that push and hold her down and prevent her from doing anything.

Lydia herself is affected by the intersection of sexism and racism. She is preyed on by a man who preys on women, but who also collects "world art" and exoticizes and consumes other cultures. Only recently have I felt that I've had a voice and a platform as a person with Asian heritage. When Lydia is starved of blood, and she has too little to feed to her larynx, she loses her voice. I wanted to explore how we can feel like we have no voice, but then discover we are still powerful, and to find that voice again.

Another intriguing element in this story is your exploration of elitism in the art world. What inspired you to set your story in this culture?

My dad is an artist from a working-class family, and he struggled a lot--first working as a pub sign painter, then a tomato picker and as a gallery assistant, all the while making sculptures in his spare time. Eventually, in my late teens, he found success. Now, his work is everywhere, collectible and well-loved. However, I saw my parents struggling to make ends meet, even while his work was in some of the top art institutions in the world. So, my inspiration for setting the book in the art world was this--my family's experience of the art industry, and my disillusionment with it; but, also, my continued love of art. Art has, for as long as I can remember, enriched my life. But the art industry is vampiric. Lydia loves art; and a lot of this book is about her discovering herself through it. But the art industry, particularly those in power, have a vampiric presence in the novel.

A book that has a vampire in it could easily be categorized as horror, but Lydia isn't really the thing to fear in this novel. It's the humans around her. --Grace Rajendran, freelance reviewer and literary events producer

Book Candy

Book Candy

Mental Floss explored "9 fascinating items that went down with Titanic," including a handwritten Joseph Conrad short story and a bejeweled version of the Rubáiyyát.

"Celebrate spring with these poetry collections for children," the New York Public Library suggested.

"Scientists develop paper from sunflower pollen that can be 'unprinted' & reused." (via Design Taxi)

A miniature manuscript by Charlotte Brontë will go on sale for $1.25 million, CNN reported.

Rediscover

Rediscover: Henry Patterson

British author Henry Patterson, who wrote 85 novels, predominantly thrillers and in the espionage genre under the pseudonym Jack Higgins, died April 9 at age 92. Patterson sold more than 250 million copies worldwide and his books were translated into 60 languages. He was best known for his World War II thriller The Eagle Has Landed, which was published in 1975, sold more than 50 million copies and was adapted into a British film of the same name starring Sir Michael Caine, Donald Sutherland, Jenny Agutter and Robert Duvall.

British author Henry Patterson, who wrote 85 novels, predominantly thrillers and in the espionage genre under the pseudonym Jack Higgins, died April 9 at age 92. Patterson sold more than 250 million copies worldwide and his books were translated into 60 languages. He was best known for his World War II thriller The Eagle Has Landed, which was published in 1975, sold more than 50 million copies and was adapted into a British film of the same name starring Sir Michael Caine, Donald Sutherland, Jenny Agutter and Robert Duvall.

Patterson's first novel, Sad Wind from the Sea, was published in 1959. Between 1959 and 1974, he wrote as many as three or four books a year. In the late 1960s, Patterson began publishing under his pen name Jack Higgins, with the first of his many bestsellers, The Savage Day and A Prayer for the Dying, coming out in the early 1970s. Other titles include Thunder Point (1993), Angel of Death (1995), Flight of Eagles (1998) and Day of Reckoning (2000). A sequel to The Eagle Has Landed, The Eagle Has Flown, came out in 1991. Patterson's final book, The Midnight Bell, was published in 2017 by Putnam ($9.99).