Friday, January 21, 2022

In the first episode of the classic British comedy series Black Books, a man rushes into the bookshop and desperately asks Bernard Black for The Little Book of Calm. The situation leaves the frazzled patron, Manny (Bill Bailey), only marginally better off for having acquired a copy. Things get more complicated when he accidentally swallows the book. In the hospital, his doctor breaks the news that "somehow you assimilated it into your system overnight."

I thought about Manny when I recently encountered a new study from the University of Oxford, University of Vienna and Nesta that noted it is "often assumed that engaging with traditional types of media improves well-being, while using newer types of media, such as social media, worsens well-being." The paper contends that "changes in the types of media people consumed and the amount of time people spent engaging with traditional media were not associated with substantial changes in anxiety or happiness levels."

Reading's job isn't to make me happy. The last six books I read were Louise Erdrich's The Sentence (Harper, $28.99); Damon Galgut's The Promise (Europa Editions, $25); Sandrine Colette's The Forests (Europa Editions, $18); Amanda Lohrey's The Labyrinth; Joy Williams's Harrow (Knopf, $26) and Muriel Barbery's A Single Rose (Europa Editions, $22), all of which, I believe, were good for my long-term well-being. If they also sparked anxiety, they meant to. Any happiness came from encountering great reads.

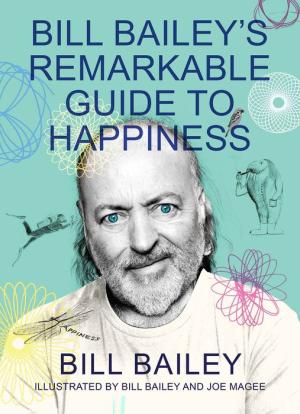

Which leads me to Bill Bailey's Remarkable Guide to Happiness (Quercus, $28.99). In his chapter on reading, Bailey observes: "There are many scholarly articles which list the benefits of reading, ranging from having a greater vocabulary to being more thoughtful towards others, or even broadening your outlook on life generally."

Which leads me to Bill Bailey's Remarkable Guide to Happiness (Quercus, $28.99). In his chapter on reading, Bailey observes: "There are many scholarly articles which list the benefits of reading, ranging from having a greater vocabulary to being more thoughtful towards others, or even broadening your outlook on life generally."

On the other hand, it was through newish media I learned, in December 2020, that Bailey had become the unlikely winner of the British TV competition Strictly Come Dancing. That was indeed a moment of profound happiness with no anxiety attached, and definitely improved my short-term well-being. --Robert Gray, contributing editor

All Day Is a Long Time

by David Sanchez

In his rich, visceral debut novel, All Day Is a Long Time, David Sanchez sketches a portrait of addiction and young adulthood that wrestles with the limitations of recovery narratives.

Sanchez's protagonist, also named David, is driven by appetite. A voracious reader from a young age, he reflects: "I would do anything to relieve that restlessness in my heart." At 14, after running away from home to follow a girl from Tampa to Key West, David tries his first hit of crack cocaine. The high catches him like a riptide, setting him adrift on a sea of addiction and precarity, doomed to "decades of misery and haste, ecstasy and boredom."

Floating between jails and treatment centers, between exhilarating benders and tedious, tenuous sobriety, David's life loses its sense of linearity. Sanchez smartly subordinates the plot to the vivid textures of his narrator's interiority; aware of the pitfalls of addiction narratives, David resists surrendering to their fatalism. "I needed some kind of agency," he protests. "I just wanted some reason that didn't lead to the dead end of predestination that haunted me everywhere I went."

Forgoing many plot beats typical of a coming-of-age story, Sanchez sets his novel to the frenetic pace of his narrator's thoughts. As he sifts through his drug-singed memories to piece together an account of himself that is free of "blame shifting" and "flimsy excuses," David's fitful passions become a genuine yearning for self-knowledge. Only David, Sanchez suggests, could author his own salvation. --Theo Henderson, Ravenna Third Place Books in Seattle, Wash.

Discover: In his debut novel, David Sanchez offers a vivid portrait of youth and addiction, as visceral as it is introspective.

When Me and God Were Little

by Mads Nygaard, transl. by Steve Schein

Mads Nygaard's When Me and God Were Little, translated by Steve Schein, is a stark portrayal of a hardscrabble childhood in a blue-collar, small town in Denmark, on the coast of the North Sea. Its narrator is seven-year-old Karl Gustav, and his distinctive point of view is filled with preposterous details that make perfect sense to him. "In our town you couldn't drown barefoot," he begins, and yet his big brother, Alexander, has managed to do just that, permanently upsetting Karl Gustav's worldview.

His father is a drunk, but owns his own business building houses, and "Our house was so big that Mom still hadn't gotten around to vacuuming all the rooms." "Dad weighed 250 pounds and it was all muscle, except for the hair," but then Dad goes to jail (something about the papers in his file drawers; the young narrator isn't concerned with the details), so Karl Gustav and his mother move into a county-owned house in a new town. Unperturbed, the child continues obsessing over soccer and terrorizing his teachers. Years pass, very few friends come and go, and readers follow Karl Gustav's experiments with porn, disastrous employment, grifting, a doomed love affair with another damaged young person and a developing relationship with his father. The loss of his brother will always loom large, for Alexander was a hero: "He just smiled, knowing everything."

This is an unusual novel, its narrator's voice colorful, unpolished and unforgettable in Schein's gruff translation. It is Karl Gustav's singular perspective that makes When Me and God Were Little the memorable, bizarre, poignant adventure that it is. --Julia Kastner, librarian and blogger at pagesofjulia

Discover: A rocky childhood on the Danish North Sea is rendered in weird but apt terms by an extraordinary young narrator.

Romance

How to Love Your Neighbor

by Sophie Sullivan

Sophie Sullivan (Ten Rules for Faking It) presents a sunny Southern California romance in How to Love Your Neighbor. Things are looking up for Grace Travis: she's close to finishing design school, she's moving into the tiny California beach house her grandparents left her and her toxic mother seems to be (mostly) leaving her alone. But Grace discovers that Noah Jansen, the handsome surfer she collided with on the beach one morning, is her new neighbor. He is stuck-up, rich and determined to demolish her house so that he can buy the property and install a swimming pool.

Sparks fly as Grace and Noah engage in a series of battles and negotiations in their ongoing war over renovations. But when Grace's best friend starts falling for Noah's assistant and love is in the air, Grace can't help but think a bit differently about Noah.

Loosely connected to Ten Rules for Faking It but easily read as a standalone novel, How to Love Your Neighbor is a fun, frothy romance. Both Noah and Grace grow as they learn more about each other and face the dysfunction in their respective pasts. Fans of Sally Thorne or Sarah Hogle are sure to enjoy the enemies-to-lovers angle, and the vibrant Southern California setting makes this an easy, breezy read. As for the design themes, anyone who has ever binged a home improvement show or spent too long on Pinterest will appreciate how the homes, as well as the relationships, are renovated. --Jessica Howard, bookseller at Bookmans, Flagstaff, Ariz.

Discover: In this wholesome enemies-to-lovers romance, two neighbors absorbed in a renovation war find love.

Food & Wine

Unbelievably Vegan: 100+ Life-Changing, Plant-Based Recipes

by Charity Morgan

Charity Morgan's Unbelievably Vegan is a welcoming collection of more than 100 adaptable vegan recipes, perfect for anyone looking to adopt a more plant-based diet. Morgan is known for cooking for professional athletes--see the documentary The Game Changers for more--but she also cooks for, as she says, "regular people looking to change the way they eat." It's this inclusive approach that makes her "Plegan" recipes so accessible: she's clear that this style of eating can supply all the nutrients even an elite football player needs, while also being simple enough to prepare in a home kitchen.

Morgan opens with the usual suggestions of kitchen tools and some easy pantry and refrigerator swaps, but the star of the book is the large section of sauces, seasonings and toppings she uses to spice up the recipes that follow. Vegan food is often maligned as boring or repetitive, and Unbelievably Vegan proves that shouldn't be the case. This cookbook is full of enticing recipes, but the genius here comes from the ways Morgan suggests to incorporate them into an existing meal routine. Building blocks such as Walnut Chorizo, for example, can be incorporated into tacos, empanadas, omelets and more.

Morgan brings readers through the day, from breakfast to dessert, with high-flavor dishes that lean on her Puerto Rican and Creole favorites. Casually styled photos accompany each recipe, making Unbelievably Vegan an inspiring feast for the eyes as well as the palate. --Suzanne Krohn, librarian and freelance reviewer

Discover: This vegan cookbook is packed with more than 100 flavorful, hearty recipes and just the right amount of guidance for readers looking for a more plant-based diet.

Biography & Memoir

Lorraine Hansberry: The Life Behind 'A Raisin in the Sun'

by Charles J. Shields

After Lorraine Hansberry's death from cancer in 1965 at age 34, her ex-husband, Robert Nemiroff, collected her writings in To Be Young, Gifted and Black. Charles J. Shields's admiring but probing Lorraine Hansberry: The Life Behind "A Raisin in the Sun" suggests that two other descriptors are critical to appreciating the playwright: Hansberry was privileged and gay.

In Shields's telling, both attributes shaped his subject's worldview. Hansberry, who was raised by upper-middle-class Republican parents on Chicago's South Side, found herself ostracized at her racially mixed school--not for being Black but for being well-to-do. After awakening to the power of the dramatic arts at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and to the ideals of the political left, Hansberry made her way to New York City, where she met and married Nemiroff, a white fellow traveler. For Hansberry, her eventual coming to terms with her sexuality crystallized the idea that racism, sexism and homophobia are three strands of one pernicious mindset.

Lorraine Hansberry exhibits Shields's pertinacious research as he proceeds toward the book's inevitable climax: with 1959's A Raisin in the Sun, which Hansberry wrote when she was 29, she made history as the first Black female playwright to have a show on Broadway. Along the way, Shields (And So It Goes: Kurt Vonnegut: A Life) keeps touching on Hansberry's artistic challenge: she was determined to inject her politics into her plays while creating realistic work that, as she wrote to her mother about Raisin, "tells the truth about people, Negroes and life." --Nell Beram, author and freelance writer

Discover: This avid biography of the Black playwright, who died in 1965 at age 34, emphasizes her artistic challenge: inserting her politics into her plays while creating realistic Black characters.

Just Pursuit: A Black Prosecutor's Fight for Fairnes

by Laura Coates

When Laura Coates transferred from the Civil Rights division to the U.S. Attorney's office, she assumed it would be similar work within the Department of Justice; however, her new role as a criminal prosecutor revealed the many ways justice is not always served, especially for Black and brown defendants. Just Pursuit: A Black Prosecutor's Fight for Fairness chronicles some of the notable cases Coates observed, times she felt torn between her duty as a prosecutor and her experiences as a Black woman. She writes, "I had been a trusted champion of people who looked like me. But now, I was often distrusted as an agent of a system that disproportionately filled prisons with people who looked like me." Ultimately, the injustices she saw and those she was obligated to participate in led her to leave the Department of Justice and pursue justice through teaching, private practice and writing.

Whether recounting the story of a mother's desperate testimony that accidentally hurts her daughter's case, or of a young man fighting to prove he has been misidentified as the suspect in a crime, Coates treats her subjects with respect and care, relaying critical details without resorting to emotional exploitation. Coates has an acute eye for gestures and dialogue, recalling each scene with uncanny precision. But Coates's narrative never rings untrue, providing a compelling reminder of the persistence of injustice in the U.S. criminal justice system. --Sara Beth West, freelance reviewer and librarian

Discover: Former Federal prosecutor Laura Coates vividly tells the difficult stories of racial injustice she experienced while at the U.S. Department of Justice.

Social Science

Manifesto: On Never Giving Up

by Bernardine Evaristo

In Manifesto: On Never Giving Up, Booker Prize winner Bernardine Evaristo peels back the layers of her literary life, exploring the childhood origins of her creativity, recounting her activism on behalf of British writers of color, and sharing the profoundly life-altering personal development strategies that guide her artistry. Fans of Evaristo's work will discover in Manifesto the passionate core of this unstoppable force in 21st-century literature.

One of eight children born to a white English mother and a Nigerian immigrant father, Evaristo (Girl, Woman, Other; Lara) grew up in '60s South London, absorbing from an early age the class, race and cultural barriers her parents overcame to build their multiracial family. A passion for history leads the author to trace her English roots back to 1703, while her Nigerian family history remains frustratingly elusive.

The author's soulful exploration of her early years, accompanied often by hilarious observations, reveal a courageous young woman who compromised nothing in pursuit of her artistic endeavors, including drama and theater. Living independently, with freedom to explore her sexuality and the privacy of a room of her own, helped Evaristo's writing blossom. Poetry offered a creative outlet for self-expression, and the city of London was her muse.

Evaristo's career ambitions are intertwined with her vision for the communities she inhabits: women, people of color, working-class and immigrant families, and older women. Her personal manifesto, summarized at the end of this remarkable book, is ripe with inspiration for those who come after her, her advice timeless and applicable to readers at every stage of their artistic endeavors. --Shahina Piyarali, reviewer

Discover: This Booker Prize-winning British author's soulful memoir captures the essence of her creativity and offers inspirational guidance to emerging writers.

Essays & Criticism

The Lives of Literature: Reading, Reaching, Knowing

by Arnold Weinstein

Arnold Weinstein, a Distinguished Professor of Comparative Literature at Brown University, has spent 50 years teaching the subject in various classrooms. In what he asserts is his final book, he reexamines those years and a life filled with literary afterlives. Weinstein (A Scream Goes Through the House; Morning, Noon, and Night) writes that literature "can be thought of as a fellowship of spirits," a fellowship that crosses time, space and experience in order to teach readers more about the world they live in.

In this volume, he describes the literary canon as an entity that "houses human lives." He considers the shared experiences of characters and their writers, and how literature "maps human dimensions." Both literary criticism and personal memoir, Weinstein's book imparts thought-provoking conversational musings that echo the lectures he gave on authors such as James Joyce, Toni Morrison, Sophocles, Mark Twain and Shakespeare, among many others. He also weaves in reflections on his experiences of teaching such authors in lectures, in large online courses, and even through the disruption of the Covid-19 pandemic.

After a long career, Weinstein contemplates how even those with depths of experience can still learn. What is found here is less hard-and-true facts about the books and authors he covers, and more a fascinating invitation to reorient oneself to what can be gained from reading and how the relationship between reader, author, character and text is constantly evolving. --Michelle Anya Anjirbag, freelance reviewer

Discover: After 50 years of teaching literature, Arnold Weinstein meditates on learning and teaching, and what literature truly gives readers.

Poetry

What Is Otherwise Infinite

by Bianca Stone

There are poems that roll along, lulling with a quiet certainty in each line, and then there are poems that strike with a blunt force, shouting questions previously unasked. Bianca Stone's What Is Otherwise Infinite does both. Divided into four sections (Monad, Dyad, Triad and Tetrad), Stone's collection is a weaving of search and rescue, of lost and found, a containing of things that cannot be contained. Though most of the more than 50 poems are in free verse with traditional alignment, some of the selections play with structure and spacing, letting the words interact with the white space in more complex patterns.

Stone (The Möbius Strip Club of Grief) regularly employs language and imagery that will be familiar to readers who have grown up in the church, lines that glance at biblical allusion or that tangle with ideas more often kept safe in a sermon. But Stone is no easy penitent, attempting "the leftover/ saggy and unreal job/ of aging/ towards benediction," convinced people are "No more miraculous/ than the plainest of birds." Her lines will also resonate with readers who want to change and don't know how, those who know both the comfort and the critique of the words, "We are all only this." Whether dealing with alcoholism, motherhood, climate change or literature, Stone faces each difficult truth. She does not shrink from the hard facts, preferring to look at them square and then allow her language to refract them back to the reader in sharp, crystalline focus. --Sara Beth West, freelance reviewer and librarian

Discover: This collection of more than 50 poems both lyrical and fierce tackles heady questions of philosophy and religion and self.

Now in Paperback

Black Buck

by Mateo Askaripour

Peppered with spit-out-your-drink absurdities and killer similes, Mateo Askaripour's debut novel, Black Buck, is an unflinching and satirical look at racism and corporate culture.

Written in the form of a how-to manual-cum-cautionary memoir, Black Buck--a Read with Jenna/Today Show book club pick and longlisted for the Center for Fiction's First Novel Prize--is about Darren, a young man from Bed-Stuy who's "fine doing my own thing" and working at Starbucks, until a tense and unusual exchange leads to a job at a startup called Sumwun.

Riotous scenes "straight out of Any Given Sunday" and seemingly supernatural portents mark Darren's transition from slinging coffee to his rapid rise at Sumwun. Despite being the only Black person in a brutal atmosphere, surrounded by co-workers who reek "of old money and blood-splattered gallows," as well as "privilege, Rohypnol, and tax breaks," Darren excels professionally.

"Every day in my house was deals day; everything was up for negotiation." "The sell" comes in many guises--not just the corporate and corner hustlers, but the activists trying to "get over" and the mother urging her child on to their fullest potential. It's hard to reconcile Darren's awareness with some of his subsequent deals with devils, yet his messiness is compelling. When it's not heartbreaking, it's certainly entertaining. The highs, lows and twists are masterfully dizzying.

Whether or not a system constructed of "rules... to make [people of color] never able to win" can be turned into a vehicle of freedom by its own means is debatable. Black Buck exhibits an enthusiastic and trenchant heart in grappling with the proposition. --Shannon Hanks-Mackey, writer and editor

Discover: Mateo Askaripour's satirical novel is the story of a young man seeking professional success and personal freedom while enduring the horrors of racism and the consequences of his own actions.

Children's & Young Adult

The Daily Bark: The Puppy Problem

by Laura James, illus. by Charlie Alder

Read all about it! Edge-of-the-seat drama, a scintillating secret, a heartwarming resolution--it's all here in Laura James and Charlie Alder's The Daily Bark: The Puppy Problem, the first offering in a chapter book series that, if its inaugural title is any indication, will feature all the canine cuteness that's fit to print.

City dachshund Gizmo is forced to move to the village of Puddle after his human, Granny, decides that country living will be better for memoir writing. In Puddle, he befriends Jilly, his Irish wolfhound neighbor, who has four pups. But Jilly has a grim report for Gizmo: "My owners are planning to sell the puppies." Jilly has an idea: she and Gizmo can trawl the village and ask the other dogs if they know of local homes for the pups. Gizmo racks up some new dog friends, but he and Jilly get nowhere with their mission. Now Gizmo has an idea: using Granny's typewriter, he creates a newspaper bulletin urging its readers to "encourage humans with dog-friendly homes to... find the puppies a home!" The success of his plan affirms for Gizmo his talent as a writer, and The Daily Bark, with its all-Puddle-dog staff, is born.

James (the Adventures of Pug series) delivers a giddy entertainment harboring a couple of serious concerns: in addition to Jilly's anxiety about being separated from her pups, there's her shame about her inability to read. As a pup protagonist, Gizmo is a winner, his appeal only enhanced by his athletic limitations, which he demonstrates with a series of pratfalls. Alder (illustrator of the Doggo and Pupper series) runs with The Daily Bark's slapstick and beguiling aspects, using firm lines filled with solid colors to show Gizmo's klutziness and adorableness to full advantage. --Nell Beram, freelance writer and YA author

Discover: This darlingly amusing first title in a chapter-book series finds a city dog and his human moving to the country, where the pooch makes new friends--and finds his professional calling.

Northwind

by Gary Paulsen

Gary Paulsen's mesmerizing modern-day epic Northwind tells a story of survival and a search for meaning in the remote wilderness of Norway's Arctic coast.

Twelve-year-old Leif is the orphaned son of an unknown man and a "sea-woman." As a baby, Leif was nursed with sour goats' milk and fed scraps, and as soon as he could walk, he was put to work on fishing boats. One day, the fishermen leave him in a far northern village with a group of "used-up and part-crippled old men" and their servant, Little Carl. There Leif and his companions are approached by a mysterious ship that brings a deadly disease to the camp. As the men die one by one, Old Carl sends Leif and Little Carl into the icy wastes on a handcrafted canoe with the admonition to "Keep going north and never come back." To survive, Leif must learn to sustain himself and live in harmony with a world that is both beautiful and dangerous.

Northwind is an engaging and powerful work with an almost ancient feel. The tale of man versus nature is as old as time, but Paulsen (Gone to the Woods), who died in 2021, goes beyond the genre by exploring the complex perspectives of animals such as whales, bears and ravens. Paulsen's use of narrative devices like kennings and repetitious phrasing hark back to epic sagas such as Beowulf and the Poetic Eddas: tides become moon-currents, silence becomes non-sound and memories become thought-pictures. But possibly the most compelling aspect of the work is the lesson Leif learns along his journey: "Don't go to a place. Go to be. Just to be." --Cade Williams, freelance reviewer and staff writer at the Harvard Independent

Discover: A powerful story of survival and a search for meaning in the remote wilderness of Norway's Arctic coast by the late Gary Paulsen.

Love in the Library

by Maggie Tokuda-Hall, illus. by Yas Imamura

"This is a true story. Mostly," Maggie Tokuda-Hall (Squad) explains in her author's note in Love in the Library, both a revealing exposé of unjust history and an exceptional tribute to love. Tokuda-Hall's maternal grandparents are Tama, a librarian, and George, the library's most constant patron. What might seem a quotidian situation is anything but: Tama and George are among 120,000 Americans of Japanese descent imprisoned during World War II at a time that "being Japanese American... was treated like a crime." The pair have been held "for a year already" behind barbed wire and towers with armed guards at Minidoka, one of 10 prison camps in the western United States. Tama's love of books sustains her through "constant questions. Constant worries. Constant fear." Also constant is George, who visits daily to check out more books. So is his big smile. Despite their abhorrent situation, Tama learns to smile back.

"Even under those circumstances, that terrible injustice, Tama and George found love," Tokuda-Hall marvels. Artist Yas Imamura (The Gravity Tree) uses gouache and watercolor to create remarkable illustrations that haunt, delight and capture the couple's "improbable joy." Imamura favors browns and greens to capture the bleak desert landscapes but includes touching details that inspire and uplift: a beloved book held tight, clasped hands, children at play, tin-can-potted blooming flowers. Most extraordinary is the breadth of Imamura's expressions. George and Tama's story is decades old, but "it's very much the story of America here and now," Tokuda-Hall reminds readers--of white supremacy, police violence, voter suppression. Finding love, as exemplified by George and Tama, is the hopeful antidote. --Terry Hong, Smithsonian BookDragon

Discover: Library books and love sustain two young Japanese Americans incarcerated during World War II in Maggie Tokuda-Hall's exceptional picture book homage to her maternal grandparents.

Anatomy: A Love Story

by Dana Schwartz

In Anatomy, Dana Schwartz (Choose Your Own Disaster; The White Man's Guide to White Male Writers of the Western Canon) pulls back the curtain on the thrilling and fascinating world of 19th-century surgeons and the bodies they dissect, as seen through the eyes of 17-year-old Hazel Sinnett in 1817 Edinburgh, Scotland. Part romance, part gory historical curiosity and part pulsating page-turner, Schwartz's novel is thrumming with life, even as it looks compassionately at what is dead and dying.

Hazel has her heart set on becoming a surgeon. It doesn't matter that no woman can be a physician, let alone a surgeon. It doesn't matter that she's the eldest daughter of a lord and the niece of a viscount, and is expected to marry well. It doesn't even matter that she's been basically betrothed since birth to her dry-as-a-bone cousin, Bernard, who doesn't want such a "morbid" wife. Hazel is determined not only to be a surgeon, but also to find a cure for Roman fever, the deadly disease that killed her older brother and seems to be sweeping Scotland again.

Hazel dresses as a man in order to attend lectures by the famed Dr. Beecham and the less-pleasant Dr. Straine. But when her true identity is revealed, she must prove her worth by passing the medical exam with no professional help. Desperate for experience, Hazel teams up with Jack Currer, a handsome and scrappy resurrection man, to dig up the bodies she needs. Fortunately, bodies aren't hard to find in a contagion-ridden city. But through Jack, Hazel begins to see there's more plaguing the streets than just Roman fever: there are sightings of strange men prowling the cemeteries, mysterious disappearances and unexplained wounds among the working classes. And as Hazel begins practicing on dead and living patients alike, she and Jack discover a secret darker than they could have imagined.

Nineteenth-century Edinburgh provides a hauntingly atmospheric backdrop to Hazel and Jack's gothic-inspired tale. Filled with secret passageways, lantern-lit graveyards and cobwebbed theaters, the novel's setting is not only delightfully textured, with its period-specific macabre aesthetic, but also rich in historical detail. Excerpts from Dr. Beecham's Treatise on Anatomy open most chapters and provide extra detail not only on the fascinating history of surgery during this period, but also on the subtly disturbing cultural, political and social underpinnings that "scientific" beliefs often uphold. Slyly intelligent in its exploration of one young woman's career ambitions and the uncanny divisions between "care" and exploitation in the medical field, Anatomy has more than its fair share of social criticism creased between pages of romance, mystery and thrills.

And, to be sure, Anatomy does pack a punch when it comes to thrills. Midnight grave robberies, the "unpleasant squelching of the blood and viscus between... fingers" and unpracticed medical students "hack[ing] away at the innards" all lead up to an appropriately blood-splattered climax. While fans might say that Anatomy is most akin to the genre-dexterous Schwartz's podcast Noble Blood--which deep-dives into the murderous lives of historical royals--it is still host to her surprising and irreverent humor (on display in her popular Twitter account @GuyInYourMFA). Schwartz's wit bubbles up at unexpected moments and often characterizes the corset-loosened chemistry between Hazel and Jack. For example, after spending a heart-pounding night hiding in a dug-up grave with an eyeless corpse, Jack (poorly) plays the part of the haunting spirit that a local priest mistakes him for: " 'Yes! We be the undead woken! And we'll be'--he tugged on Hazel's arm--'going now. Arghhhh!' "

These moments of lightness pair with more barbed jabs at Hazel's betrothed, Bernard, the novel's incarnation of Schwartz's favorite target: the privileged white man who, though self-assuredly uptight, could be knocked over by a breeze. Bernard begins the novel as the seemingly innocuous butt of Hazel's internal jokes: "He was nice enough, his skin relatively clear. He was, well, dull, but so were the rest of them." As with all truly great humor, the jokes at Bernard's expense become increasingly earned as well as unsettling when the true extent of the societal power given to such a frail man becomes apparent.

Thus, as with all of Schwartz's work, there is more to Anatomy than immediately meets the eye. Like Hazel, readers may begin the book eager to indulge in the strangely pleasurable and fascinating experience of witnessing grotesquerie. Hazel admits that after receiving a missive describing a hanging, she "had read [the letter] so many times she had memorized every line: the way the convict's head had jerked when the rods were lowered to its temples, how its eyelids had scrolled open." But also like Hazel, the reader's awareness of such violence as people being "trotted out for yet another performance, yet another matinee for yet another crowd" begins to transform the way one consumes the novel's gore. The true heart of Anatomy lies in Hazel's compassionate, patient-centered approach to medicine and the knowledge that living bodies are animated not only by organs, but by those for whom they care. --Alice Martin