Tuesday, August 3, 2021

Books for early- and pre-readers cover a wide range of topics, such as things that go, counting, even baking. Here are some titles focused more on fun than fundamentals.

Role-Playing Games by Molly Rossiter and illustrated by BlueBean (Starry Forest Books, $8.99) is one in a series of board books for "Gamer Babies," which also features Chess and the soon-to-be-published Video Games. The book semi-sneakily attempts to teach readers how to play role-playing games ("Choose who you want to be.... What gear will you take on your adventure? Roll the die to see") but will most certainly be best loved by caretakers who enjoy role-playing games themselves. What better way to introduce your little one to your favorite pastime than to make it their favorite board book?

Role-Playing Games by Molly Rossiter and illustrated by BlueBean (Starry Forest Books, $8.99) is one in a series of board books for "Gamer Babies," which also features Chess and the soon-to-be-published Video Games. The book semi-sneakily attempts to teach readers how to play role-playing games ("Choose who you want to be.... What gear will you take on your adventure? Roll the die to see") but will most certainly be best loved by caretakers who enjoy role-playing games themselves. What better way to introduce your little one to your favorite pastime than to make it their favorite board book?

In Blankie, a Narwhal and Jelly board book by Ben Clanton (Tundra Books, $8.99), Narwhal has a blankie that can double as all kinds of things: a hankie, a hat, a flag, a bag. Clanton's signature thickly lined protagonists on blank backgrounds delight in all the different things they can turn a blankie into. Young children and adults can take blankie ideas from Narwhal and Jelly or maybe even make up some of their own.

In Blankie, a Narwhal and Jelly board book by Ben Clanton (Tundra Books, $8.99), Narwhal has a blankie that can double as all kinds of things: a hankie, a hat, a flag, a bag. Clanton's signature thickly lined protagonists on blank backgrounds delight in all the different things they can turn a blankie into. Young children and adults can take blankie ideas from Narwhal and Jelly or maybe even make up some of their own.

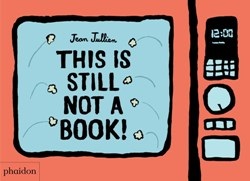

Jean Jullien's This Is Still Not a Book! (Phaidon Press, $16.95) is, well, still not a book. It's an open mouth eating popcorn, a flip phone (an imaginary item pre-readers will likely never see), a pajama top and an open suitcase, among many other things. Pulling up a flap reveals an elephant's long nose; turning the page probably (definitely) kills that mouse in a mouse trap. Every page is a new story and a new chance to engage with a child. --Siân Gaetano, children's and YA editor, Shelf Awareness

Jean Jullien's This Is Still Not a Book! (Phaidon Press, $16.95) is, well, still not a book. It's an open mouth eating popcorn, a flip phone (an imaginary item pre-readers will likely never see), a pajama top and an open suitcase, among many other things. Pulling up a flap reveals an elephant's long nose; turning the page probably (definitely) kills that mouse in a mouse trap. Every page is a new story and a new chance to engage with a child. --Siân Gaetano, children's and YA editor, Shelf Awareness

The People We Keep

by Allison Larkin

It is 1994 in Little River, N.Y., when 16-year-old April steals her neighbor's car to drive into the next town for an open mic night. She returns the car when she's done, but the teasing taste of freedom she finds on the road--and the crowd's positive reaction to her songs--set the standard for the rest of this propulsive novel. Allison Larkin's The People We Keep is the story of April's journey away from Little River: escape, both seeking something (home, community) and fleeing from it.

Her mother is long gone and barely remembered; her father alternates between abuse and neglect, but he also gives April her first guitar. It is clear that her music is essentially her only lifeline. April finds her first hope and solace in Ithaca, a town with hippies and colleges and baffling coffee drinks, and where she gets a job and a lover and makes her first true friend. Thanks to her past and trauma, though, she both yearns for and fears attachment; she has to keep moving.

The People We Keep is intimate, urgent and direct; April's first-person voice is magnetic, compelling. Just when it begins to feel like she'll never learn to stop moving, she makes a discovery. "We have people we get to keep, who won't ever let us go. And that's the most important part." This is a novel of great empathy, about connections and coming of age, built families and self-acceptance. --Julia Kastner, librarian and blogger at pagesofjulia

Discover: In this propulsive, empathetic novel, a teenaged singer-songwriter takes to the road, both hoping for and running from an experience of love and acceptance.

The Bloom Girls

by Amy Pine

A.J. Pine is known for writing steamy romances and series fiction featuring sexy cowboys (Only a Cowboy Will Do). However, in The Bloom Girls, she delivers a vibrant standalone novel that mines contemporary family dynamics as mother and daughter both fall in love and embark on new life chapters.

When Gabi Bloom graduates from college, her academic milestone reunites her parents, divorced since Gabi was four. Her mother, Alissa, a 39-year-old bakery owner in Chicago, forfeited her own dreams to raise their daughter alone while her ex-husband, restless Matthew, traveled the world. After graduation, Gabi, an aspiring photographer, sets off on a two-month-long European adventure, where she meets and falls for Ethan, a U.S. expat. Their whirlwind romance leads to an engagement. When Gabi returns home with Ethan as her fiancé, Alissa and Matthew, who had a one-night stand the night of Gabi's college graduation, hide the news that they are now expecting a baby.

As the family, including extended members prone to meddling, plan a traditional Jewish wedding with a host of amusing trappings, Alissa and Matthew play a romantic tug-of-war. They continue to hide the pregnancy--trying not to overshadow the nuptials--while dealing with their rekindled feelings, battling the past and confronting issues of trust.

Pine delivers a tender, fun, engaging story that insightfully depicts turning points of unexpected romance and how deciphering what one truly wants out of life can be challenging at any age. --Kathleen Gerard, blogger at Reading Between the Lines

Discover: A tender, fun story in which a mother and daughter both face life-changing romantic dilemmas.

Paris Is a Party, Paris Is a Ghost

by David Hoon Kim

In 2007, the New Yorker published "Sweetheart Sorrow," which became the first chapter of David Hoon Kim's enigmatic debut, Paris Is a Party, Paris Is a Ghost. The duration of the novel's opening 30ish pages is the only time Fumiko--a Japanese student in Paris who was the protagonist's lover--is actually alive, and yet her presence looms throughout.

Henrik Blatand is a multiply-displaced, peripatetic polyglot: he's ethnically Japanese, adopted to Denmark (with a brief educational foray in Sweden), currently not working on a literary thesis in Paris. His fleeting affair with Fumiko ends with her suicide, an event from which Henrik can't seem to recover. She appears as a corpse for a dissection class in the second chapter--although Henrik will never know her afterlife fate, as one of the students assigned to parse Fumiko's inert form takes temporary narrative control. When Henry returns to continue his story, he's an untethered wanderer, often chasing Fumiko's elusive, impossible image. His most significant relationship after Fumiko is with his goddaughter, Gém, the precocious child of a classmate.

Trained at the Sorbonne and Iowa Writers Workshop, Kim, like Henrik, is a multilingual expat-in-motion. Kim was born in Korea, raised in the U.S. and educated in France, and he is fluent in Korean, English and French. His erudite prose is undeniably sublime and polished, but there are also distracting missteps and disconnects in this debut. The exquisite beauty of his composition--combining words, crafting sentences--however, bodes well for perfecting future narratives. --Terry Hong, Smithsonian BookDragon

Discover: David Hoon Kim's ambitious debut follows an ethnic Japanese expat in Paris as he loves and then mourns a young woman lost to suicide.

Mystery & Thriller

Rabbit Hole

by Mark Billingham

British author Mark Billingham (Bloodline; Their Little Secret) takes a break from his 17-novel series about DI Tom Thorne for his fifth standalone novel, which grippingly explores Det. Constable Alice Armitage's psychotic breakdown after witnessing her police partner's murder. Rabbit Hole charts Al's downward spiral with drugs, alcohol, casual sex and an altercation with her boyfriend, until she's given "medical retirement" from the police, then admitted to London's Hendon Community Hospital, suffering from PTSD.

Denied her request to be discharged, Al focuses on solving the murders of a patient and a senior nurse, but her help is rejected. The staff tries to keep her away from the police detectives, who don't acknowledge knowing her or respect her investigative skills. Once popular with the hospital staff, Al risks their ire with her investigation, interviewing other patients and personnel. Her own mental state, she reasons, gives her insight into her fellow patients' motives.

In Rabbit Hole, the complicated Al becomes the ultimate unreliable narrator, as she works through her precarious psychological problems, invigorated by the chance to use her cop skills, aided by her sarcastic wit. Billingham successfully makes Al both appealing and irritating as her anger issues erupt even more while the police ignore her theories. Al's realization that no one wants her to solve the murders shapes her character and her recovery. The novel expertly delves into daily life in a psych ward where drugs and routine rule over treatment, and Rabbit Hole's stunning finale puts a new spin on Al and the plot. --Oline H. Cogdill, freelance reviewer

Discover: In this gripping standalone from British author Mark Billingham, a former police detective admitted to a psych ward tries to solve two murders while working on her own mental health.

Graphic Books

It's Not What You Thought It Would Be

by Lizzy Stewart

Award-winning British children's author/illustrator Lizzy Stewart makes an impressive adult graphic debut with interlinked short episodes observing, analyzing and celebrating women's friendships. The nine chapters in It's Not What You Thought It Would Be could each stand alone, but Stewart cleverly relies on shades of orange to signal narrative connections that, combined, reveal a story of two friends from inseparable childhood to youthful estrangement to exuberant reunion.

The opening chapter, "Heavy Air," introduces the first of two girls anticipating great change: "there is a new world and it is completely different." Best-friendship happens as Stewart introduces the girls together in close-up, expression-filled panels in "Dog Walk": one is teased for being "sensible," the other wants to embody "cool." Five years later, in "A Quick Catch-Up," the girls have matured into young adults--one stayed home, the other got out; Stewart amplifies their fraying relationship with intense hues on rougher surfaces. The friend-who-left reappears--Stewart garbs her in orange for easy recognition--in the titular "It’s Not What You Thought It Would Be," which follows the lives of three close London women. Eight silent years follow the uncomfortable catch-up, until the ex-bffs reconnect in "The Wedding Guests." In between the friends' evolving relationship, Stewart inserts four interstitial interludes that read like gentle reminders--for her characters and readers both--to look out and beyond.

Each chapter is an experiment in presentation: POV shifts from first-person to omniscient, brushwork fluid to exacting, panels simplified to detailed. Yet Stewart's reliable orange palette keeps her girls-to-women narrative readily discernible. Her compassionate depictions of women alone, women together, will undoubtedly find welcoming audiences. --Terry Hong, Smithsonian BookDragon

Discover: Lizzy Stewart cleverly examines the ebbs and flows of women's relationships from childhood to adulthood in her insightful adult graphic debut.

Two-Week Wait: An I.V.F. Story

by Luke C. Jackson and Kelly Jackson, illus. by Mara Wild

The intimate struggles of a husband and wife desperate to become parents might not be universal literary fare, but with millions of couples worldwide attempting conception via IVF, Two-Week Wait will surely, deservedly find sympathetic audiences. Luke C. Jackson and Kelly Jackson "began their own IVF journey in 2011 and are now parents of two daughters"--transparently revealed on the first page. They share those experiences through a fictional lens in a debut graphic novel in collaboration with multimedia artist Mara Wild (who happens to be Luke's former student).

Conrad and Joanne once felt they had "all the time in the world" to have kids. They met in university, married, have "good jobs," Joanne says, and are "relatively together people," Conrad adds. After a year of trying (and too much "medical googling"), Joanne laments her "officially geriatric" eggs. Their ordeal of becoming parents requires invasive tests, hormones and procedures, yet even more challenging is the emotional roller-coaster of waiting and hoping, and finding the tenacity to try again (and again).

The couple remains forthright throughout: their envy over friends' pregnancies and others' children, the financial drain, the toll on their professional and social relationships, asking for help from parents as 30-somethings. They consider giving up--even on each other. Wild reflects these ups and downs, highs and lows, with a palette of mostly grey-to-blues and salmon-to-reds, drawn in flowing strokes and layered shadows, from markedly different points of view--from the side, from above, as if visual reminders to consider all angles. The creative trio's combined efforts provide an insightful, moving tale. --Terry Hong, Smithsonian BookDragon

Discover: A couple draws on their own experiences with parenthood via IVF to create this intimate graphic tale.

Run: Book One

by John Lewis and Andrew Aydin, illus. by Nate Powell and L. Fury

The March trilogy was a magisterial, National Book Award-winning achievement that provided an accessible and dramatic narrative account of John Lewis's involvement in the civil rights movement. The trilogy concluded with one of the movement's greatest triumphs, the passing of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Run: Book One picks up where March: Book Three left off, as reactionary forces pushed back against the movement's successes and the movement itself began to splinter. Published after Lewis's death in 2020, Run: Book One is a reminder that the story of the civil rights struggle does not have a neat ending; for Lewis and so many others, the work never ended.

The graphic novel opens with an ominous sight: the title of the book is announced over a two-page spread of Ku Klux Klan members marching. It makes for a disturbing reversal of the many scenes of civil rights marches in the previous trilogy, with Georgia KKK Grand Dragon Calvin Craig even shown co-opting Lewis and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee's (SNCC) own tactics as he instructs his marchers: "If you might become too... emotional, please stay behind. There'll be no catcalling, no responding if anyone hollers at you." Run quickly establishes that soon after the passing of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, forces were gathering to fight back, and those forces would make use of a variety of strategies in addition to brute violence.

The art in Run: Book One maintains a similar style to the March trilogy: black and white and cleanly drawn, with the lack of visual clutter putting an emphasis on realism and legibility. These books are drawn in a way that both carefully documents history--the many historical figures are recognizable and easy to distinguish--and also provides an accessible reading experience. In the March trilogy, artist Nate Powell was gifted at showcasing the inspiring sweep of protest marches, as well as the solidarity and discipline of the marchers. Here, Powell and L. Fury use their talents to show the strength of the forces arrayed against civil rights activists like Lewis.

At the same time that reactionary forces were gathering, divisions were growing within SNCC under the chairmanship of Lewis. As violence intensified in the cities, the doctrine of nonviolence preached by Lewis and Martin Luther King, Jr., began to fall out of favor. Disagreements about strategy, tactics and even ideology intensified as firebrands like Stokely Carmichael began to use slogans like "Black Power" that had greater appeal to the young and angry. All of this dissension is portrayed through John Lewis's eyes, manifesting as a rising tide that he can do little to stop. As Lyndon Johnson's administration became increasingly unreachable and noncooperative, there arose an increasing sense that Black Americans needed to make change on their own. While Lewis remains gracious toward his rivals, extending a great deal of understanding to the roots of their anger, he makes his dismay clear at the emotionally charged debates that rocked SNCC, the aggressive power grab that lost him the chairmanship, and the loss of the "unity of purpose" that propelled the march from Selma.

It is here that Run is at its most personally devastating, showing how Lewis's exhaustion at the physical demands of his job was accompanied by a kind of spiritual exhaustion, a powerlessness at watching an organization that he helped build leave him behind. Even more than the trials and tribulations depicted in the March trilogy, Run: Book One feels like a true dark night of the soul for Lewis, as his loneliness and alienation become increasingly apparent. After Lewis leaves SNCC, one panel shows him halfway through a set of double doors, looking back inside, toward the light, while holding a box filled with his things. Even depicted at a distance, in profile, we see the regret and exhaustion in Lewis's downcast expression and his slightly hunched posture. Outside, we see nothing but darkness, while Lewis reflects:

"A riot is the language of the unheard," Dr King would say. "What is it that America has failed to hear?" And as Dr. King felt the movement slipping away, my life as I knew it was over. And I could feel everything slipping away... I was twenty-six years old... I was broke... I had no job... For my entire adult life, the movement had been my family. I had no wife... No children... No place to even call home anymore."

Run is more than a personal narrative, of course, providing a valuable history of a period that is often skimmed over in textbooks, explaining the roots of the Black Power movement, the Black Panthers and the turn toward more militant activism. At the same time, we learn about the ways reactionary forces sought to limit the effects of the Voting Rights Act through violence and intimidation, as well as more subtle means. The authors and artists don't shy away from obvious parallels to the present day: from the voter suppression that followed the Voting Rights Act to acts of police violence that precipitated explosions of rage in the cities. Equally valuable for those studying John Lewis's life are the lessons he has to offer about the difficulties of organizing and activism, such as the way divisions over strategy can widen into impassable differences. The ending of Run: Book One promises a pivot, as Lewis's inexhaustible career continues into a new phase in New York City. Over time, we know Lewis will find incredible political success, but Run: Book One is a valuable reminder that even heroes like John Lewis faced crises that they couldn't resolve. --Hank Stephenson

Essays & Criticism

Agatha Christie: First Lady of Crime

by H.R.F. Keating, editor

"What are Agatha Christie's chances of survival as a writer who will be read a century from now?" asked crime-writing scholar Julian Symons in his essay "The Mistress of Complication," which appeared in 1977's Agatha Christie: First Lady of Crime, edited by H.R.F. Keating. It's easy to picture Symons's brow furrowed in uncertainty as he posed this question but, of course, he needn't have worried that Christie's readership would dwindle. Nearly half a century later, and with countless Christie film treatments, television adaptations and continuation novels since Symons wrote his essay, there's a new generation of Christie fans, and they should cheer the re-release of Keating's invaluable anthology.

Each of Agatha Christie's 13 contributors--a significant number of them crime writers--stakes a claim on a fresh angle: there's one essay each on, among other topics, theatrical productions of Christie's work, film treatments of her fiction and the role of music in her stories. More than one writer touches on Christie's rumored Hercule Poirot fatigue, how her familiarity with poisons from her Great War training as a nurse informed her plots, and whether the ending of 1926's The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, which made her name, was a cheat. It's a good bet that even the most ardent Christie-philes will learn something from Keating's book, whether it's that the Queen of Crime liked to write her novels in cheap hotels or that--mon Dieu!--Hercule Poirot was at one point to be portrayed on film by the comic actor Zero Mostel. --Nell Beram, author and freelance writer

Discover: First published in 1977, this reissued anthology honoring the Queen of Crime is a trove of fact, observation and scintillating conjecture.

Health & Medicine

Inflamed: Deep Medicine and the Anatomy of Injustice

by Rupa Marya and Raj Patel

Inflamed: Deep Medicine and the Anatomy of Injustice invites readers on an illuminating journey through the human body, exploring the inflammatory damage wrought by poverty, racism and injustice. Rupa Marya, a physician, and Raj Patel (The Value of Nothing) encourage a renewed, post-pandemic reckoning with ongoing systems of oppression.

"Inflammation" is used as a medical term as well as a metaphor for the damaged state of our overheated planet as Marya and Patel take aim at the dehumanizing impact of colonialism's promotion of profits over people, exploitation of resources over preservation. Modern medicine, a product of this mindset, dispenses treatment to individuals without regard to their ancestral trauma or history, and it is unable to heal what truly ails them. No chemical, the authors explain, can erase the cumulative burden of exposures from before birth or remove social, ecological or economic injustice.

Marya and Patel are compelling storytellers; there is a steady brilliance to their writing as they blend scientific research, patients' anecdotes and oral histories to set forth a prescription for repairing relationships damaged by systems of domination. It begins with small acts, such as attaching patient photographs to CT scans to promote physician empathy, and expands to actively challenging air and noise pollution in poor neighborhoods, predatory lending, incarceration of minorities, the monocropping of foods, the clear-cutting of forests, the wage gap and attempts to control women's reproductive power.

Visionary in scope, Inflamed will ignite dynamic conversations toward a boldly sweeping movement of restoration and healing through active decolonization. --Shahina Piyarali, reviewer

Discover: This compelling work of medical analysis illuminates the destructive impacts of modern-day colonialism and proposes ambitious strategies for improving planetary health.

Poetry

Pilgrim Bell: Poems

by Kaveh Akbar

Pilgrim Bell, the second poetry collection by Kaveh Akbar (Calling a Wolf a Wolf), is a playful and profound meditation on life as a Muslim American.

Scriptural themes and echoes abound here. Prose poem "The Miracle" is about Muhammad the Prophet, an illiterate man who nevertheless read God's words at an angel's command. Akbar ponders the fears and addictions that hold people back from assenting to revelation. The multi-part title piece probes identity, forgiveness and vulnerability. Its short, punctuated phrases suggest timid determination: "All day I hammer the distance./ Between earth and me./ Into faith." Yet cynical skepticism is never far behind; "Ask me again/ about my doubt--turquoise/ today and almond-hard," he invites in the later poem "There Is No Such Thing as an Accident of the Spirit."

Farsi is a recurring point of reference, and "There Are 7,000 Living Languages" and other poems attest to the relativity and sensuality of language. The final entry, "The Palace," presents the USA as a land of opportunity--but with costs. Akbar's father left Iran not knowing if he'd ever see his siblings again. How was this immigrant family to feel at home when some Americans casually joke about bombing the poet's birthplace of Tehran?

Food, plants, animals and the body supply the book's imagery. Wordplay and startling juxtapositions ("my turn-ons/ include Rumi and fake leather") lend lightness to a wistful, intimate collection of 35 poems that seek belonging and belief. Readers should get a mirror out to read "In the Language of Mammon"--it's printed backwards--but keep it at hand for reflecting on their own challenges of faith and family. --Rebecca Foster, freelance reviewer, proofreader and blogger at Bookish Beck

Discover: An Iranian American poet imparts the experience of being torn between cultures and languages, as well as between religion and doubt, in this gorgeous collection of confessional verse.

Children's & Young Adult

I Am the Subway

by Kim Hyo-eun, transl. by Deborah Smith

The Seoul subway system's line #2 is a circular route that's also the city's busiest; it happens to include Gangnam--as in "Gangnam Style"--among its dozens of popular stations. Author/illustrator Kim Hyo-eun's magnificent I Am the Subway highlights a train traveling along the clockwise inner circle, with passengers--rushing, relaxing, attentive, distracted--continually boarding and disembarking as they move about their day. Each gets a moment to share their thoughts, while the subway's lulling "ba-dum, ba-dum" resonates throughout. Deborah Smith, co-winner of the 2016 Man Booker International Prize for Literature, lyrically translates this Korean bestseller.

Kim's prosaic journey begins before the title page as the subway introduces itself, preparing for another new day: "Around I go.... Crowds of people wait to climb aboard." And then we're off! Mr. Wanju is running late again, already intent on finishing work to hasten home to his lovely daughter. Granny steps on soon thereafter, laden with gifts from the sea for her family. Doors open for a busy mother of two, a shoe-repair shop owner, an exhausted student, a glove salesman. Kim insightfully acknowledges "the unique lives of strangers you might never meet again" on spread after spectacular watercolor spread, the diverse passengers each caught in a single moment in time. Kim's author's note mentions how her father taught his children to see many things; those details--"things not visible to the eye but still significant"--are exactly the elements that stupendously enhance each page: different gaits of people in motion, phones galore, bags and packages and various expressions. Lucky readers, climb aboard: extraordinary explorations await. --Terry Hong, Smithsonian BookDragon

Discover: This enchanting picture book shares empathetic stories of passengers on Seoul's busiest subway line.

Paola Santiago and the Forest of Nightmares

by Tehlor Kay Mejia

In this fantastical, funny and heartwarming sequel to Paola Santiago and the River of Tears, the plucky protagonist seeks answers about her connection to the paranormal.

Even though 12-year-old Paola Santiago defeated the legendary ghost La Llorona, she feels invisible. Her mom ignores Pao while acting all "Suburban Susie of the PTA" for a new guy. And Dante, who kissed her cheek last summer, seems embarrassed by Pao. When new nightmares begin worrying her, she visits Dante's abuela against his wishes. Señora Mata tells Pao to find her father for answers or he will "topple the world." Then she collapses. Pao, believing her estranged father can tell Pao who she is and also help Señora Mata, recruits Dante (still on his "Pao-is-the-source-of-all-suffering-in-the-world routine") to find him. But the way is impeded by vicious fantasmas and painful grudges that will test Pao's resilience.

Tehlor Kay Mejia impresses with this moving middle-grade fantasy deeply rooted in Mexican American culture. Her Latinx cast criticizes racism and police bias ("How were you supposed to get care for the people you loved when the 'care' dispatched was equally likely to kill them?") while Mejia incorporates myth (a shapeshifting hitchhiker) and magic (dream travel). Pao's beautiful problem-solving mind and personal growth (including learning Spanish) shine, and her tension-relieving quips ("I'm a self-taught seventh-grade scientist, not a white lady with a podcast about true crimes!") temper heartbreaking moments. Paola Santiago and the Forest of Nightmares is a satisfying follow-up, full of heart and humor that celebrates Mexican heritage, family and forgiveness. --Samantha Zaboski, freelance editor and reviewer

Discover: In this lively middle-grade series sequel, Paola Santiago braves a journey filled with frightening fantasmas and familiar friends to find a cure for an ailing abuela and the truth behind her dreams.