|

|

Andrea Curtis is an author whose work has been published around the world. Her subject matter is wide and varied but includes nature writing, architecture, literature, food, history, and women's health.

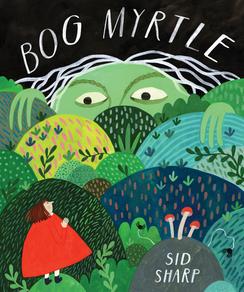

Sid Sharp is an artist and illustrator from Toronto who makes drawings, paintings, and comics. Their interests include folklore, horror stories, mysterious and unknowable things, and finding good sticks for their stick collection.

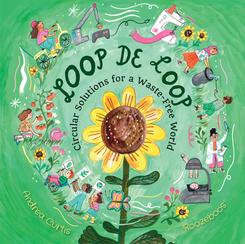

Andrea Curtis's Loop de Loop (illustrated by Roozeboos) is a picture book from Groundwood Books that discusses "circular solutions for a waste-free world"; Sid Sharp's Bog Myrtle from Annick Press features a forest spider obsessed with sustainability. Here the authors talk about balancing the macabre and upsetting realities with hope and humor for young readers.

Andrea Curtis: Hey Sid! I'm a big fan--I love the terrifying but fair Bog Myrtle as well as the adorable dancing scaredy sheep in The Wolf Suit. Your books teeter between subtlety and sharpness. I'd love to know how you think about this balance when you're making books for children.

Sid Sharp: I'm a fan back! Your writing is so smart and direct but also full of kindness--it makes sense to me that you're thinking about that balance.

I've always loved gloomy and off-kilter things, and I think kids' books are so interesting for that sensibility. On the one hand, I get to be very dramatic and over-the-top about my gloominess, especially in the illustrations, which is so much fun. On the other hand, I'm portraying a version of the world to people who haven't been alive for all that long, so I really want to make sure that the world has buoyancy and hope and friendly people in it. I think that second want is what guides the writing for me.

Loop de Loop also had to strike a balance between some grim realities about the present and a hopeful vision of the future. What leapt out at me was the way you write about a waste-free world not as what COULD happen, but what WILL happen. Is it important to you to be plucky, rather than mopey, about the need for sustainability?

|

|

| Sid Sharp (photo: Liam Coo) |

|

Curtis: When you say that, the first thing that pops into my mind is the union-organizing spiders in Bog Myrtle. I imagine them with picket line posters: "Pick plucky!" or "I'm down with mopey!"

I'm not sure I'd be able to choose a team. I don't really think about the climate emergency in that way. I have lots of fears and worries and I allow myself to sit in grief and mopeyness about it. But I also look for hope. I see the innovations and resilience of people, and know, as a student of history, that when we come together, we can change lots of things for the better.

In terms of how I write about this for kids, my baseline is that I think children are very smart and can be extremely nuanced thinkers. Unlike a lot of adults, they are willing to accept that two things can be true at once. For instance, Magnolia is a money-hungry meanie AND Beatrice loves her sister anyway. Or: we are in a spiraling climate disaster AND there is hope for change. Lots of people believe we shouldn't burden kids with heavy topics in children's books. I'm not one of them. You?

Sharp: I mostly think of how I would have felt, as a kid, had there not been any stories with that kind of edge available to me--I would have hated it! I agree that kids are smart. They know when it's time to put a book down because they're feeling afraid, and they know it's something they can pick back up later.

It's probably not surprising that I read a lot of folk tales (Bog Myrtle is very loosely inspired by a Hans Christian Andersen story), and I'm a big fan of Maurice Sendak and Roald Dahl. I think the book that scared me the most as a young kid was Hershel and the Hanukkah Goblins by Eric Kimmel and Trina Schart Hyman, which I absolutely loved.

|

|

| Andrea Curtis (photo: Jenna Muirhead) |

|

Curtis: I also really like folk tales. Do you know the terrifying love story "The Green Ribbon" from Alvin Schwartz's In a Dark, Dark Room and Other Scary Stories?

Sharp: Yes! I think "The Green Ribbon" brought me to "Bluebeard," which became an all-time favorite. There's this feeling of deep, silent mystery that I always try to evoke in my paintings of the living, watching forest.

Curtis: You definitely do this. I really enjoyed the idea that nature is not passive--it notices and retaliates when pushed too far. I'd love to hear how you developed the characters of Magnolia and Beatrice.

Sharp: I have a lot of affection for Magnolia, who is kind of an exaggerated version of my grumpy moods--probably this is why it was important to me to let her hang out scowling in a stomach at the end instead of truly vanishing. And Beatrice is how I'd like to be, unshakeable and eternally optimistic. Even though the two of them end up in this outlandish simulacrum of boss and union leader, I like that they also have their own personalities and eccentricities separate from the metaphor.

It feels like the "characters" in your book are really the reader, or maybe a sense of the collective, which is cool.

Curtis: I like that idea! It's true that there isn't a traditional character in my text, though the brilliant illustrator Roozeboos created some excellent characters. There's a butterfly that loops through all the pages (even underwater with a snorkel) in a kind of Where's Waldo? adventure, and a little girl character whose journey we also track. Plus, there's a beautiful "Easter egg" Roozeboos included, featuring the eight-year-old girl whose memory the book is dedicated to. Aliyah was the daughter of friends of mine and a fierce environmental activist. Tragically, she died while I was writing the book, but Roozeboos included her throughout, a tribute to her continued impact in the world through her family's effort to share her passions.

Sharp: Whoa, that's beautiful. I love Roozeboos's illustrations; they have a living, spontaneous feeling to them.

Curtis: What's interesting to me is that both of our books--utterly different in look and tone and feel--have surprisingly parallel journeys as we both take on these big issues. I think the line "We aren't separate from nature. We are nature" in Loop de Loop is the beating heart of the book. There is a similar line in Myrtle: "We all share the forest, every creature and forest and flower and shrub. It shelters us and it feeds us and it gives us what we need to take care of each other, and in return we need to leave it better than we found it."

Sharp: I love that! Different winding paths to the same destination.