|

|

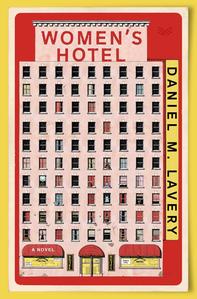

| Daniel M. Lavery (photo: Eustache Boch) |

|

Daniel M. Lavery is beloved for his intelligent humor and insightful observations honed through years at The Toast and as Slate's Dear Prudence advice columnist. His bestselling Texts from Jane Eyre and Something That May Shock and Discredit You proved his nonfiction skill, and with his first novel, Women's Hotel (HarperOne), he aims "to meet historical fiction on its own terms," introducing readers to a memorable cast of characters making their homes in a New York City residential hotel in the 1960s.

There is a certain tone in your work--slightly elevated, slightly detached, and utterly hilarious. Has this writerly voice always come naturally, or is it something you've cultivated?

It is something I have cultivated, particularly for Women's Hotel. In the last five years or so, I've spent a lot of time reading reissues of novels by minor women writers from the 1920s to the 1960s, titles like The Day of Small Things by O. Douglas, about these snobby Scottish aristocrats who are slightly down on their luck but handle their degradation with graciousness and do a few small things. I love that tone, that style of writing. It's a tone that I associate with mid-century domestic fiction, so that's something I wanted to hone in Women's Hotel.

I also think about Jane Austen, the way her work takes aim at a tight-knit community full of people that you do, in fact, care deeply about, but who behave in ways that make you hate them. And yet you can't bear your own hatred for them. You have to see them tomorrow. There's humor in that, born out of an intimate knowledge of other people, an inability to get away, and a need to find some sort of resolution that feels light. Like with Kitty--she's always looking for an angle, asking for something, and the other characters, especially Katherine, try to navigate her neediness politely. Someone who's not willing to be rude is often a good source of humor.

Like Austen, Women's Hotel focuses on traditional, domestic issues (changes to breakfast, dating, marriage, clothes), with economic precarity as a constant undercurrent. What role did women's hotels play in providing opportunities to women in the early stages of financial independence?

Like Austen, Women's Hotel focuses on traditional, domestic issues (changes to breakfast, dating, marriage, clothes), with economic precarity as a constant undercurrent. What role did women's hotels play in providing opportunities to women in the early stages of financial independence?

I wanted money and expenses to be present throughout the book. For these women, living in the city is affordable, but a lot of the social structures that would have underpinned their lifestyle in the '20s and '30s are no longer there. The guaranteed weekly rate of a Biedermeier room can help somebody hold on toward the end of something and enable others to jump up a little further; for others, they're treading water, just a step away from sliding downwards.

Being in a residential hotel removes you briefly from a recognizably domestic sphere, but you still have to know where you're going to get your meals, to figure out how to relate to the people around you, to decide what kind of relationship you're going to have to the marriage plot, and so I wanted there to be a sense of maybe I can get away from those sort of questions for a while, but they're not going anywhere. They're just outside the door.

Of the residents, Katherine is my undisputed favorite, especially due to the authenticity of her journey. Do you have a favorite? Was any character more delightful to write than the others?

I also have deep affection for Katherine. Her backstory took up more pages than I had originally anticipated, but I was really happy with it. In some ways, I think Gia might have been the most fun. It's like she was airlifted in from a totally different book! She knows what she wants, and everything goes exactly according to plan. She's like a Dale Carnegie character come to life! So that was quite a lot of fun. Similarly, I think Lucianne is a character who was a lot of fun, in part because she spends so much time with people she's also thinking about undermining. She likes them, but she's also just wondering about how to dress in such a way that will make her look better than Pauline or make Katherine look like a dead bird.

Yes! We know so much about Katherine, as you note, and with Gia, we get a few fairly intimate details but only as it relates to her particular project. That partial intimacy really works with the hotel setting, where some people become something of a fixture and others drop in and just as quickly drop out, known for little more than the way they look in the hallways--completely real and completely mysterious at the same time.

Gia is one of a handful of characters inspired by real people. She's loosely based on a writer named Joan Brady. Ten to 15 years ago, Brady wrote an essay called something like, "I married my mother's ex-lover, and I'm not sorry!" The basic outline was that her husband, writer Dexter Masters, had previously dated her mother, they didn't see each other for a decade, and then they connected in the city and hit it off. I took it in different places, making it Gia's goal the whole time, but I love that unapologetic Oedipal notion.

For Gia, if you're beautiful, you're a ballet dancer, you control your body perfectly, then you also control the world around you perfectly--it's the fantasy of somebody who really does get everything she wants. She says, I want to live with the man that I love and I want to die in the penthouse of an expensive hotel. So for her, her trajectory out of the women's hotel just takes her into a better hotel, which is very different from the other character who marries toward the end of the book. She moves in with her husband and mother-in-law, and for those left behind, there's a real sense of "we're losing you." With Gia you're taking this to its highest logical conclusion: you're going to live in the sky and have gold shoes.

What was your research process like?

For the first six months, I was at the New York Public Library every weekend doing research. I read archived newspaper and magazine articles, and a lot of books, deciding what kind of people I want to include, what kinds of movements or experiences would feel meaningful or important. For instance, Jimmy Breslin and the backdrop of the newspaper mergers, which we see in Lucianne's story. I had to verify details like when did the New York Horse Show move out of Manhattan? What types of restaurants were around the '50s and '60s (the NYC streets as well as the decades)? It's always possible to do more research, so at a certain point you just have to say what I know, I know, and I want to write something now. --Sara Beth West