|

|

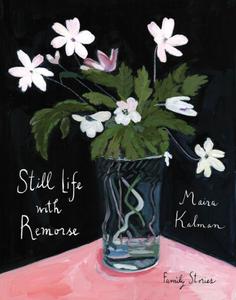

| Maira Kalman (photo: Kimisa H.) |

|

With more than 30 books for children and adults to her credit, as well as fine art exhibitions, New Yorker covers, and contributions to the New York Times, Maira Kalman has created images, often accompanied by wise, pithy, hand-lettered words, that are familiar to millions of readers. Still Life with Remorse: Family Stories (Harper, $35; reviewed in this issue) will delight fans of The Principles of Uncertainty and Women Holding Things. Here Kalman discusses the importance of still life paintings when pondering tales of remorse, plus music and walking.

How did you arrive at the title for the book?

I was hearing the word remorse everywhere I went, and I was reading it everywhere. And it seemed as if I had edited out all other words but remorse. At the same time, I was very interested in what it meant just to paint still lifes, and what it meant to just focus on the pleasure of painting flowers or a bowl of fruit, and what that kind of attention means--attention to detail and attention to the beauty of what is there. And attention to the tenderness.

I thought it was a perfect counterpoint. I was painting still lives, which had nothing to do for the most part with the stories. But they offered a kind of contemplative moment to think about what's around you, outside of you, and then to think of what's inside of you.

Tell us about the pairing of the image of the bowl of cherries on the red table with the white cloth over it, and the way that you pulled that into the story of your sister and polio and Picasso wooing Françoise Gilot.

Well, it started with Cézanne's cherries, of course. There was a beautiful show [of Cézanne], and I went back five times just to stare at that bowl of cherries. It was a watercolor or a gouache maybe. And the sense of whatever that was, of that moment from a hundred and more years ago, this is the meaning of life.

And then the story gets built in its way, which I hope has some humor in it, of course. And some tragedy, or pathos. I like to cut away and cut away as much text as I possibly can. So there's air and there's a sparseness.

Part of it is a mystery. How does a story come from somewhere into your brain? It's so lovely.

One still life that radiates that sense of remorse is the bouquet on the cover that accompanies the Kafka family story.

One still life that radiates that sense of remorse is the bouquet on the cover that accompanies the Kafka family story.

My son, Alex Kalman, who designs my books, and I decided that one said the most and would be very arresting on the cover.

But I have to say about Kafka--he's an obsession. And I just want to put in a plug for the new translation of Kafka's diaries by Ross Benjamin, where he pretty much has everything that was in the original [diaries] and that had been a little bit sanitized by Max Brod and other translations. It's just fantastic.

What resonates throughout [The Diaries of Franz Kafka] is that inconsistencies--being funny and smart and stupid and passionate and lazy, all of those things--are contained within a human being.

One of my favorite phrases in your book is "the possible-probable remorse tense," which comes up in "Uncle," when he almost gets lost at sea, and also in "Mrs. Pearlman's Son," who "could have drowned" at the beach.

In my family, and in many families, there's some sense of, oh, we're always on the brink of disaster, and we don't know how that will reveal itself during the day. And if it doesn't, it could have. We could have fallen on the street when we went to the post office, and we didn't, but we could have. And it's so present, this danger. And of course, you say, how dangerous can the day be, because the day is full of beauty and charm and delight.

But it's a counterpoint. As one gets older, those fears, what could be fraught in the day, reveals itself or presents itself. And you go, whoa, I could have, but I didn't. And I'm so happy I didn't, but ooh, I'm exhausted from what could have been, but wasn't.

You've written about your father before in The Principles of Uncertainty, and there you painted a portrait of him. But in this book, you tended to paint objects that told something about the people you discuss, like the bouquet that your father left for your mother.

When you look at old photographs, they're the snapshots of your life, obviously, moments frozen in time that you may or may not remember. Most of the time, I don't remember. Of course, when we were children, there's so much that happens. I wanted to write more about my father because I felt that he was always getting short shrift. And my mother was always the center of the story, the golden center.

So I had remorse about my father. And I think that it's not solved, it's not cured. It's just put into a place like, oh, this is really something that's very heartrending. And it's part of my story and part of my family story. So I was happy to give him some more attention.

And his story is so remarkable, that he and his brothers would leave Belarus and his parents stayed behind with their dry goods store and then perished in the Holocaust.

When I say that disaster lurks everywhere, I always say that the family lullaby was that we were in danger, and my father would tell us at night that anybody could come and kill us. So it wasn't some kind of conceptual idea. Despair and being destroyed by history and being destroyed by displacement echoes, of course. And then you respond to it, sometimes kindly, sometimes unkindly.

People often ask me, well, what's the difference between remorse and regret? And I say, regret is "I regret I can't join you for dinner." Remorse is "I'm sorry I ruined your life." There's a difference in the intensity. And usually remorse means you're deeply sorry for what you did to somebody else, or what you didn't do for somebody else. Even though--as I say in the book--at the time, there was no other choice. You couldn't do it, you couldn't be kinder, you couldn't be magnanimous. It seemed to be the right thing to do, whatever that was for anybody. And then you look back 20 or 30 or 50 years later and go, well, what else could have happened? But it's something that you say, look at what damage gets done. It's notable. Some people get over it, some people don't get over it, you know?

What was the inspiration for the musical interludes?

Well, music accompanies me all day long when I'm painting, there's music on, and it's mostly classical. And I say, "I want that piece for my funeral." My son and daughter are delighted to hear me ruminate about that all the time. The essence of music is so important. When you're eating ice cream, you can't be sad. I defy you to be sad when you're eating ice cream. The same thing about music. If you just allow yourself to listen to music, the emotions that go through you take you to a different place.

And those musical interludes are bittersweet, too.

Right, exactly. It's not as if all of a sudden you're laughing and jumping for joy. But you don't feel alone and you enter into this extraordinary world that gives you some kind of relief from your pain or worries. It's phenomenal. I believe that music can save your life, and I believe literature can save your life, and walking can save your life... and love, and work. And I'll go on with a list of 50 other things. I don't know what the antidote to remorse is, but I do know that there are things that you can do in your day that are just sublime. One of them is walking. And if you go to the arts, it's tangible. --Jennifer M. Brown, reviewer