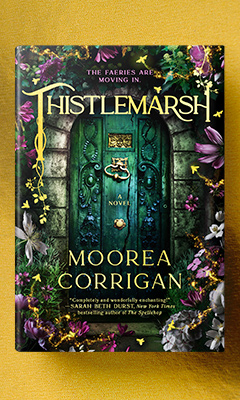

Thistlemarsh

by Moorea Corrigan

"The war did not bring the Faeries back to England. As boys languished in the trenches, they still spoke in hushed 'what ifs' until all hope ran out. The belief in magic was replaced by the reality of mustard gas." These opening lines set Moorea Corrigan's Thistlemarsh squarely in a 1919 England at once recognizable and entirely foreign, imagining a moment in history marked as much by Faerie magic--and its sudden disappearance--as by the brutalities of World War I.

Against this backdrop, a young woman named Mouse is summoned back to her uncle's estate upon his death, where she is issued both an inheritance and a challenge: Thistlemarsh Hall, a Faerie-blessed and once-esteemed manor house in the English countryside since fallen into disrepair, and a requirement to fully restore it within a month in order to secure her inheritance and the title of Lady Dewhurst. While she cares not a whit for the house or title, the bequest includes enough income to keep her brother, gravely injured at the front and with no remembrance of her, in good care for the rest of his days--and that's all the motivation the scrappy Mouse needs to try everything in her power to secure the inheritance. The task--set by her "cold, cruel, and unfeeling" uncle both to punish Mouse and to subvert the laws requiring a Faerie-blessed house like Thistlemarsh to be passed down to the nearest living heir--is daunting. Perhaps even impossible: Thistlemarsh "teetered on the brink of extinction, its bones set back against withered grounds.... It was as though the Hall was sinking into the earth." Mouse was a nurse in the war, not a carpenter, upholsterer, builder, or craftsman, and with her brother lost to the war, she's left alone to face the task set by her uncaring relative. But when a Faerie lord named Thornwood makes an unexpected appearance in her garden--the first Faerie appearance in more than a century--Mouse sees a possibility of success.

Once a student of Faerie anthropology, Mouse is well aware of the longstanding "sense of distrust" between Fae and human. While she--like so many others--had once hoped Faeries would return during the war to support their English compatriots, that hope has long since been dashed. Faeries are known to be tricksters, incapable of lying outright but fully able to deceive by omission, assumption, elision. One must never tell a faerie one's name. And "lastly, and most important of all, never trust a Faerie completely."

Despite every warning in Faerie lore, even in the books of Faerie history passed down from her late mother, Mouse agrees to bargain with Thornwood. When the house seems to push back against Thornwood's magic, however, the two are forced to work ever more closely together to accomplish their goal of restoration (and inheritance). But at what cost? How much is Mouse willing to sacrifice for success, and how entangled is Thornwood within that?

In Thistlemarsh, Corrigan has crafted a singular novel, parts cozy, Fae-inspired fever dream, enemies-to-lovers romance, historical fiction, fantasy. These elements combine to great effect: the bits of the story that feel foreseeable are reminiscent of the best cozy mysteries, with leads chasing down seemingly disparate clues only to find they are all important details, while elements of fantasy and magic keep the novel from ever falling into predictability. A series of tasks challenge Mouse and her fairy lord to untangle the magic in the hall, drawing on the best of trials in literature. And while history books don't often recall a time "when the road between the mortal world and Faerie was still clear," Corrigan draws deeply on accounts of World War I injuries to paint a picture of the cruel toll of war. Mouse toils away in a postwar hospital, where the "rush of triage work had slowed into the painful languidness of chronic care... [in a ward with] the dust of dashed dreams poisoning the air."

Corrigan sets the magic of Thistlemarsh in a world both familiar and firmly rooted in history, accomplishing a kind of fantastical worldbuilding that allows for easy entry, yet never feels oversimplified. The rules of Faerie magic here draw on common fairy tales, myths, and lore that span centuries, yet Corrigan has made this magic, and Mouse's quest to untangle it, entirely her own. "Magic is a conversation," Thornwood tells Mouse--a dialogue of wants and needs, haves and have nots, demands and expectations, and above all, power. With a sense of place so vivid that Thistlemarsh Hall often feels like a character unto itself, Thistlemarsh is an invitation to a world both old and new, imagining the story of a scrappy, fierce young woman determined to make--and claim--a place for herself and those she loves, no matter the cost. --Kerry McHugh