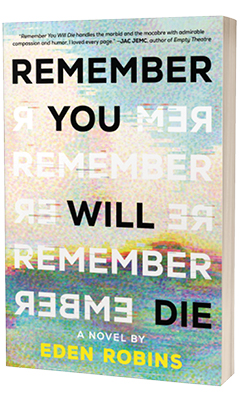

Remember You Will Die

by Eden Robins

Eden Robins (When Franny Stands Up) has written a smashingly good second novel, an utterly imaginative, genre-defying masterpiece: Remember You Will Die. Her blunt title is an accurate barometer that the end is nigh. In fact, the dead populate most of these pages. Their stories are revealed predominantly through obituaries that range from deeply soulful to delightfully guffaw-inducing. In between are occasional newspaper articles, lists, notes, word etymologies, and other ephemera that highlight death. Loosely, cleverly bound together, the narrative that emerges spotlights a singular mother/daughter relationship that will require 300 years of background to understand.

On November 6, 2102, an article appears in the New York Dispatch entitled "Mystery Surrounds Report of Girl Drowned in East River." According to an eyewitness to the watery plunge, the apparent action seems self-driven, complete with an alleged suicide note that was folded in the shape of an airplane and thrown toward the shore. Both paper and body remain missing. An anonymous call from a blocked number produces "the only concrete clue to the girl's identity": she was called Poppy.

Robins then inserts the first of multiple, fascinating etymologies. The word is, logically, "poppy": as plant ("flowers... with valuable narcotic properties"); as history ("the wanton brutality of the British Empire during the Opium Wars"); as symbolism ("of battlefields and war dead... possibly as far back as the time of Genghis Khan"). Robins also appends meaningful example sentences: "History wants poppy to be a symbol: of war, death, intoxication, resurrection. But poppy means only itself. Her needs are simple; she tilts her smiling face to the sun." These etymological interruptions are many; readers are encouraged to pay close attention to the wide-ranging background and usage of these singled-out words because prescient hints, clever asides, and a-ha revelations will be shared in each lexical intermission.

Two related obituaries follow. The first is a highly personal 1864 tribute for a 39-year-old floriographer devoted to roses--and divining young ladies' fortunes--who dies far too young on the battlefield. The second appears again in the New York Dispatch, 12 days after the opening article, and is the official obituary of Poppy Fletcher. Her "existence was little more than rumor," but her short life--a mere 17 years--is pieced together from scant details: "Her birth was unregistered, and no formal documentation has been discovered, no birth certificate or social security number, no school enrollment forms. Only a single photo of Poppy as a toddler, discovered in the cell phone of a deceased man who claimed to be a former neighbor, offers any physical evidence of her existence." One fact is certain: Poppy is the "sole offspring of the fugitive AI known as Peregrine," who was herself "a rogue science experiment" of computer scientist Matthew Fletcher, who was both Peregrine's "maker and 'consort.' "

In under a dozen pages, Robins establishes the central Peregrine/Poppy mother/daughter relationship. To tell their story, she deftly constructs a historical trail encompassing multiple centuries, conceives pioneering science, flags tragic dysfunctions and disconnects. If that's just the novel's very beginning, imagine what more Robins will concoct in the 300 pages that follow. One by one, each obituary comes closer to divulging the multi-layered origins of how Peregrine was created, how she defied her detractors, and manifested into a feeling, thinking, adaptable body able to create human life. Robins skillfully weaves together characters, relationships, events--dropping clues throughout via those slyly relevant etymologies (collapse, fathom, peach, latent, escape)--and makes the impossible believable.

Robins is a mischievous writer, detouring and distracting readers with mad scientists, performance artists, and fake deaths. Anne Frank survives to become an octogenarian, although her daughter (allegedly fathered by a priest) only made it to 42. Robins just as convincingly plays solemn soothsayer in contemplating fatal school shootings that continue decades into the future, Earth's ongoing destruction, the ruinous colonization of potential faraway alternatives. Tragedies loom, but humor--poignant, gentle, sardonic--is never far: a mortician goes by the online handle "the_decomposer"; a bar has the strippers sing and the customers strip; and the widow of the world's richest man has a "mycorrhizal network" experiment buried next to a McDonald's parking lot. Every inventive obituary is a connective micro-story of loss, grief, celebration, and regret, with surprising glimmers of hope.

So much happens. And eventually, it all makes satisfying, rewarding sense. Robins invites audiences along to experience the less-than-straightforward connectedness of humanity's past, present, and future. Time, alas, always proves fatal because "the only certainty is death, and the only other certainty is uncertainty." Yes, everyone dies, but Robins magnificently ensures their legacies linger. --Terry Hong