|

| photo: Ian Byers-Gamber |

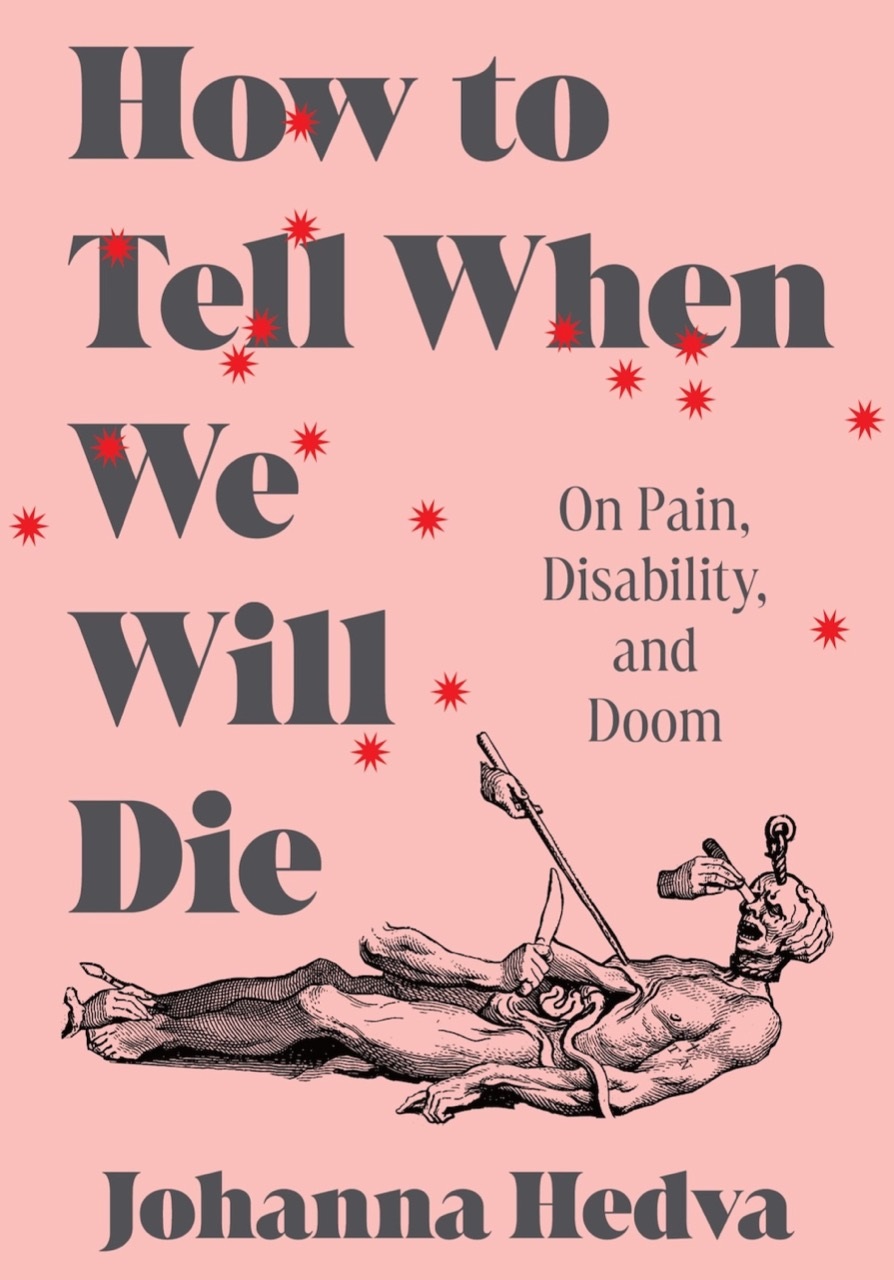

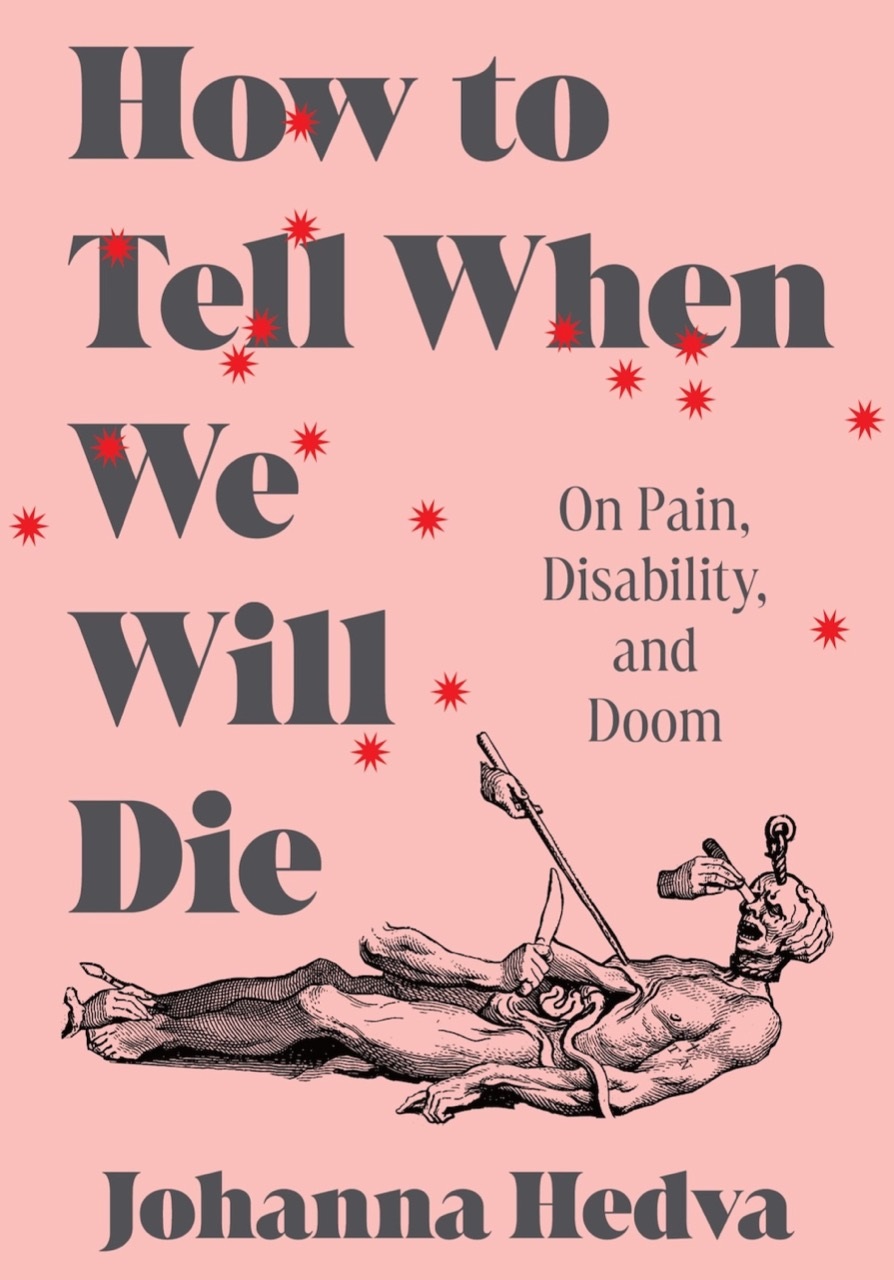

Johanna Hedva is a Korean American writer, artist, and musician who was raised in Los Angeles by a family of witches and now lives in L.A. and Berlin. They are the author of the novels Your Love Is Not Good and On Hell, as well as Minerva the Miscarriage of the Brain, which collects a decade of work in poetry, plays, performances, and essays. Their artwork has been shown internationally, and their albums are Black Moon Lilith in Pisces in the 4th House and The Sun and the Moon. Most recently, Hedva is the author of the essay collection How to Tell When We Will Die: On Pain, Disability, and Doom (Hillman Grad, September 24, 2024), which aims to detonate a bomb in our collective understanding of care and illness, showing us that sickness is a part of life.

Handsell readers your book in 25 words or less:

I wanted to tell all the many possible stories that are enlivened not despite illness and disability, but because of it.

On your nightstand now:

With Bloom Upon Them and Also with Blood by Justin Phillip Reed is probably the best thing I read last year and which, several times a week, I keep needle-dropping into just to be reminded of how cool it is. I'm reading The Plague by Jacqueline Rose; the chapter on Simone Weil is fire. It's making me reread Weil, particularly her collection Waiting for God. I'm reading this alongside Jacqueline Rose's earlier collection On Not Being Able to Sleep.

I just started The Long Loneliness, Dorothy Day's memoir, because I think my next book will be about terrorists who think of their acts of civil disobedience as "divine obedience," so I'm in the cute research phase. Also dipping into Joy Williams's Ninety-Nine Stories of God for that vibe. I recently finished Daddy Boy by Emerson Whitney and Split Tooth by Tanya Tagaq--adored both. Y/N by Esther Yi was another recent standout. I got halfway into Notice by Heather Lewis but need a little break--I'm a bit heartbroken and ran through these days, so I love this book but it's also giving trauma that my devastated guts can't totally bear in one go. Oh, and I just blitzed through two novels: Little Rot, the new Akwaeke Emezi, which I really appreciate for its depravity; and Hunchback by Saou Ichikawa, which took my whole-ass mind away from me in a shit-hot explosion that I am grateful to have been eviscerated by.

Favorite book when you were a child:

In my early 20s, I reread The Wall by Marlen Haushofer every year for five years. This was before it had been reissued, and very few people knew about it. It came to me because I was at a very grown-up party and chatting with a poet and her partner, a translator. The poet was in her 40s and dressed in burgundy and purple. The translator had written a Ph.D. on the last paragraph of On the Road. These kinds of people. They were telling me I had to read this novel called Die Wand (in German), The Wall in English, but then they got in a fight about how much or little to tell me about it. One of them wanted to tell me about it, and the other was adamant that I should know nothing. They reached a compromise: the poet told me it was "unspeakably beautiful," and the translator told me it was "about animals." I often give this book as a gift. I gave it as a birthday gift to the woman who would later break my heart. She told me she couldn't get through the first five pages; I should have known she'd break me.

Your top five authors:

Clarice Lispector, Yoko Tawada, Kim Hyesoon, Simone Weil, and Sylvia Wynter.

Book you've faked reading:

All the "best novels" written by white men.

Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for:

Darkly: Black History and America's Gothic Soul by Leila Taylor is my favorite example of a book that imbricates cultural, social, and political criticism with memoir and autobiography. The insights in it are worth the cost of the earth.

Book you've bought for the cover:

The 1972 Touchstone edition of The History of Western Philosophy by Bertrand Russell with the Jason Fulford photograph. Just a lonely-ass road leading nowhere.

Book you hid from your parents:

Going Down with Janis by Peggy Caserta, which is a grimy memoir by Janis Joplin's lover. One of the books I read as a teenager that made me gay. I remember the first line was something like, I was stoned out of my mind on heroin and Janis was giving me head, and I had never heard a woman say "head" about another woman, and in my mind I could see their sleazy hotel room, and how they broke each other's hearts, and I knew what that scene smelled like, and I was like, ohhhhhh I'm gay.

Book that changed your life:

Where Europe Begins by Yoko Tawada was my first encounter with Tawada and it made me unknow everything I knew about plot, story, sentence. It's a touchstone; I return to it all the time and have for years. It also brought me to other writers who do similar magic: Mariana Enríquez, Bora Chung, Cristina Rivera Garza. I'd also add The Door by Magda Szabó to this.

Favorite line from a book:

How cruel to make me choose one! I'll be basic and go with the line that changed every queer I know, including me, from Robert Glück's Margery Kempe: "Gender is the extent we go to in order to be loved."

Five books you'll never part with:

Okay, I am envisioning this question's premise is that I'm shot into space on a one-way mission toward a black hole, and I will need to bring books on the ship to provide spiritual relief as I hurtle toward my ultimate end. Bleak!

I'll cheat and bring all three volumes--in one boxed set!--of the Library of America's The James Baldwin Collection, for a last feeling of purpose.

Japanese Death Poems: Written by Zen Monks and Haiku Poets on the Verge of Death, compiled by Yoel Hoffman, for a last breath of peace.

The Mirror of Simple Souls by Marguerite Porete, for a last flash of beauty.

Not a book, but if I'm flying toward the terminal eclipsing of my very self, I must have access to Prince's 2007 halftime show. That's the last thing I want to see, hear, and know before the end, because, to quote Frida Kahlo's last words: "I hope the exit is joyful and I hope never to return."

Book you most want to read again for the first time:

The Limit by Rosalind Belben, one of the funniest and most grotesque accounts of illness I've ever read, and also one of the most smutty. And--not a book but a long essay that absconded with the top of my head: "Blackness and Nothingness (Mysticism in the Flesh)" by Fred Moten.

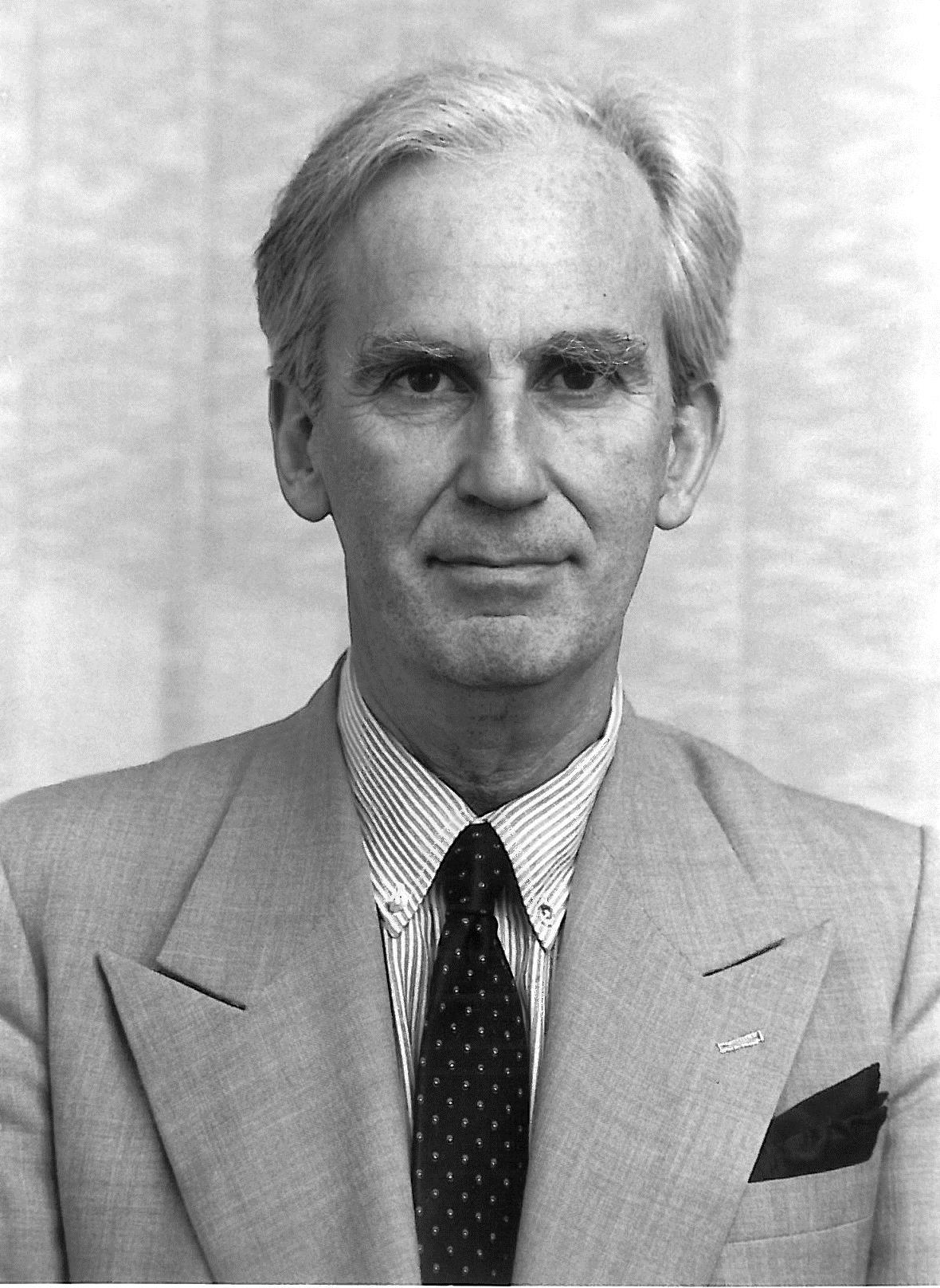

Books I've bought for the author photo alone:

In a used bookstore in New Orleans, I bought an old hardcover collection of Truman Capote's nonfiction, The Dogs Bark, because in the author photo Capote has a raven on his shoulder, and the motherfucking caption says, "The author with Lola." Oh. My. God. There's even an essay in the book about how he came to have a pet raven named Lola, and it's one of my favorite pieces of writing ever.

I rarely read cis-male authors, but I have an armchair theory that if one of them is photographed with an animal sitting on his person in his author photo, then he's exempt from the category of male author. Tarjei Vesaas, for example, has a large cat coiled around his shoulders and neck; The Ice Palace is one of the greatest feminist novels of all time, and I think the choice to include the cat in the author photo has something to do with that.

Two new positions have been created in Simon & Schuster corporate marketing that "will allow us to excel and accelerate our growth, while leveraging and supporting the great work the Corporate Marketing Team has been delivering," Wibke Grutjen, senior v-p, global chief marketing and communications officer, wrote in a memo to staff.

Two new positions have been created in Simon & Schuster corporate marketing that "will allow us to excel and accelerate our growth, while leveraging and supporting the great work the Corporate Marketing Team has been delivering," Wibke Grutjen, senior v-p, global chief marketing and communications officer, wrote in a memo to staff.

Shelf Awareness for Readers, our weekly consumer-facing publication featuring adult and children's book reviews, author interviews, backlist recommendations, and fun news items, is being published today. Starred review highlights include

Shelf Awareness for Readers, our weekly consumer-facing publication featuring adult and children's book reviews, author interviews, backlist recommendations, and fun news items, is being published today. Starred review highlights include

"The other night I had to leave late, and looking at the shop in the dark with the windows lit so prettily made my heart swell.

"The other night I had to leave late, and looking at the shop in the dark with the windows lit so prettily made my heart swell.  Mapping the Holy Land: An Illustrated Atlas

Mapping the Holy Land: An Illustrated Atlas

Book you're an evangelist for:

Book you're an evangelist for:  Beth Kander's I Made It Out of Clay is a lovely, absorbing novel of grief, dark humor, and love and friendship, with a dash of magic.

Beth Kander's I Made It Out of Clay is a lovely, absorbing novel of grief, dark humor, and love and friendship, with a dash of magic.

What goes better with coffee than a good book?

What goes better with coffee than a good book?  Capturing both the spirit of the season and National Coffee Day,

Capturing both the spirit of the season and National Coffee Day,