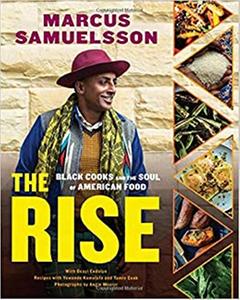

For his latest cookbook, The Rise (Voracious/Little, Brown, $38; reviewed below), featuring inspired recipes alongside profiles of Black American culinarians, chef Marcus Samuelsson collaborated with writer Osayi Endolyn. Shelf Awareness spoke with them about their research and writing process, as well as their aims for The Rise as it enters the world during a year defined by a pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement.

|

|

| (photo: Angie Mosier) | |

Marcus Samuelsson was born in Ethiopia, raised in Sweden, and currently resides in Harlem, where he runs the restaurant Red Rooster. He has opened restaurants around the world and traveled throughout the United States for his PBS series No Passport Required. His other books include the memoir Yes, Chef and The Red Rooster Cookbook.

When did you first start thinking about writing this book?

Marcus Samuelsson: I've been in the space for 25 years and also evolving as an individual. As I evolved through the 2000s, I started asking myself, here are all these incredible people that I've met along the way. They either cooked with me, their parents owned a mom-and-pop, or they're amazing writers.

The Rise is about presenting Black excellence, one. Then second, take back the authorship of American food where Black excellence and Black chefs have done incredible contributions. For me, it's very important to create content that I feel taps a void.

What was the writing and recipe development process like--and the collaborative nature of it?

Samuelsson: Osayi, Yewande [Komolafe, who collaborated on recipe development] and myself--you're looking at three Black people in the food space. Our journeys are vastly different. Yewande's expertise, specifically in West African cuisine, is far beyond mine. Osayi's know-how in non-chefs, for example, is much better than mine--and obviously coming at it from a journalist's point of view and asking other questions.

There're so many curveballs to it, too. We thought we were done and then... the pandemic, which obviously impacts the Black and brown community very differently. Here we go again with something that impacts us differently. So now it took a whole other turn.

What added impact do you hope The Rise will have going into the world right now?

What added impact do you hope The Rise will have going into the world right now?

Samuelsson: I think you have to look at it from short-term and long-term. Short-term awareness: it hopefully leads to new opportunities for not just the people in The Rise but for Black and brown chefs on a local level.

And in the long term, it's about rewriting us back into American history. We know about regional Italian food. We know about regional Southeast Asian food or Japanese food. But we don't know about regional Black food. We know the difference between ramen and soba, but we don't know the difference in terms of how Creole cooking is very different than low country.

One of the distinctive motifs in The Rise is music. In your description of the Roasted Cauliflower Steaks with NOLA East Mayo, you write, "I imagine a brass band, a second line, the Neville Brothers and Lil Wayne. My stomach is nodding along with the music." How did music and food become so connected for you?

Samuelsson: Being Black--especially being in a white country--I had to constantly define my level of normalcy. So, music was that thing. You came to our home, Miriam Makeba was playing, Marvin was on the speakers, Prince constantly in my sister's and my room, A Tribe Called Quest. When I looked at Blackness and excellence, it was through music.

My goal one day is that when you look up Black food, you can define it the way you can define music. When you look at American music, the way it's divided between gospel, R&B, rock and roll, hip-hop, etc., those are promises to a sound, but it's almost like a pantry of flavors. We're not there yet with how we define our food. I hope one day.

Who or what is inspiring how you're cooking right now?

Samuelsson: I'm inspired by us. When I speak to Mashama [Bailey], she's got a book coming up. When I speak to Kwame [Onwuachi], he's cooking more than ever. If I call Eduardo [Jordan] right now, he's cooking. Patricia [Gonzalez], 18 years old, she's in my kitchen cooking. Covid is here, but it hasn't stopped us. Yes, we have this horrible, horrible, horrible thing, but I think that so much energy has been also given to us through the movement of Black Lives Matter. I'm inspired by the movement of us telling our stories.

---

|

|

| (Lucy Schaffer Photography) | |

The winner of a 2018 James Beard Award, Osayi Endolyn is a writer whose work has appeared in the Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, and many more publications. Living in Brooklyn, N.Y., she is currently working on multiple collaborative books as well as a solo one, coming from Amistad in 2022.

What excited you or intrigued you when you heard about the project?

Osayi Endolyn: I was really excited about the ability to explore in cookbook form a collection of experiences that conveyed the range and diversity of Blackness and food in this country. I think it's always been over-truncated. To put all these stories together, at the very least, asks a reader to consider what they think of when they try to define Blackness--and it's indefinable in its expansiveness. This seemed like an incredible opportunity to continue to help shape a conversation that many people had been contributing to for a long time but to do it in a way that someone like only Marcus can.

How did the people you spoke to feel about being interviewed--about having parts of their stories represented and their voices amplified?

Endolyn: The conversations were wide-ranging. Sometimes I found people were almost a little mystified at how interested I was in what they ate growing up, and what foods landed on their dinner table, and the food stories that they recalled. I had to really push in some of those conversations to ask people to not dismiss whatever it was their family practices were or whatever that food was. I saw that even for people at this level in their careers, there was still a way that we were sometimes minimizing ourselves--minimizing our stories.

I came on board in this project in late 2017. I think from where we started with these early conversations to where we are now, it does feel very powerful because I don't know that the political value of this book was as demonstrably there for people at the outset as it is now.

We're seeing finally some beginning of what looks like a reckoning in food media, in response to the Black Lives Matter movement. I wonder how hopeful you are about how real that change is.

Endolyn: It's really hard to say because we've always been very good at making exceptions out of people. I grew up most of my life throughout California. I was often the only Black person in rooms or spaces, and so to me it's not that exciting to have just one of us, or a couple of us. Yes, I celebrate individual wins--my own and others. I celebrate collective opportunities. I really work behind the scenes very hard to ensure that folks know what their options are in terms of who they bring on board for different projects and what they can ask for and what they can push back against--and it's still very hard. It's still very hard.

There is real personal and structural interrogation that needs to happen. I would say that I think the opportunities are available for people to create the change they say they want to see and that I'm not yet convinced. I hope to be a part of this ongoing shift, but the gradual, exceptional nature of it is dissatisfying even with all the successes. The parity is still far from being present. --Sylvia Al-Mateen, freelance reviewer and editor